Modeling Non-linear relationships

Modeling Non-linear relationships

Learning objectives:

Be able to implement common approaches for modeling non-linear relationships between \(X_i\) and \(Y_i\)

- Polynomials using the

polyfunction in R - Splines using the

nsfunction (splines library) - Smoothing splines

- Polynomials using the

- Understand how model predictions are constructed when using polynomials or splines

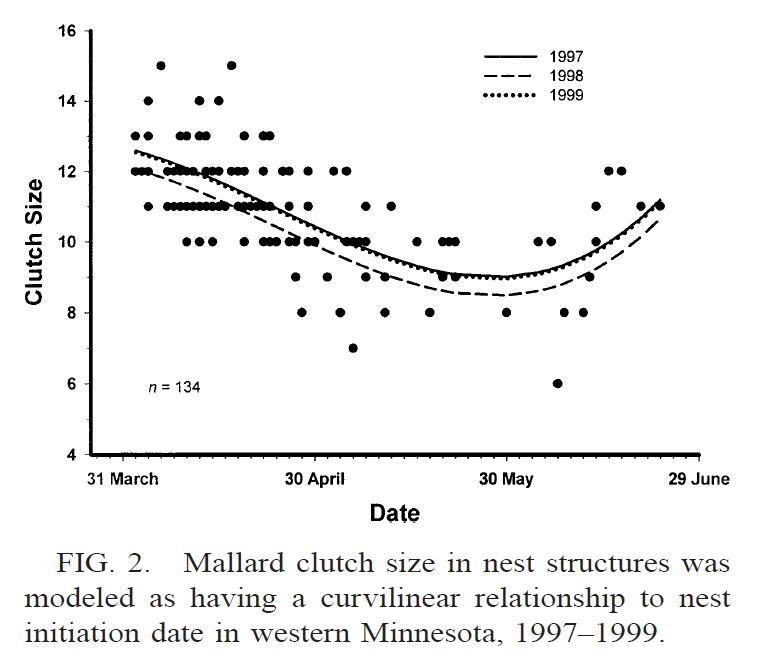

Mallard clutch size versus Julian Date

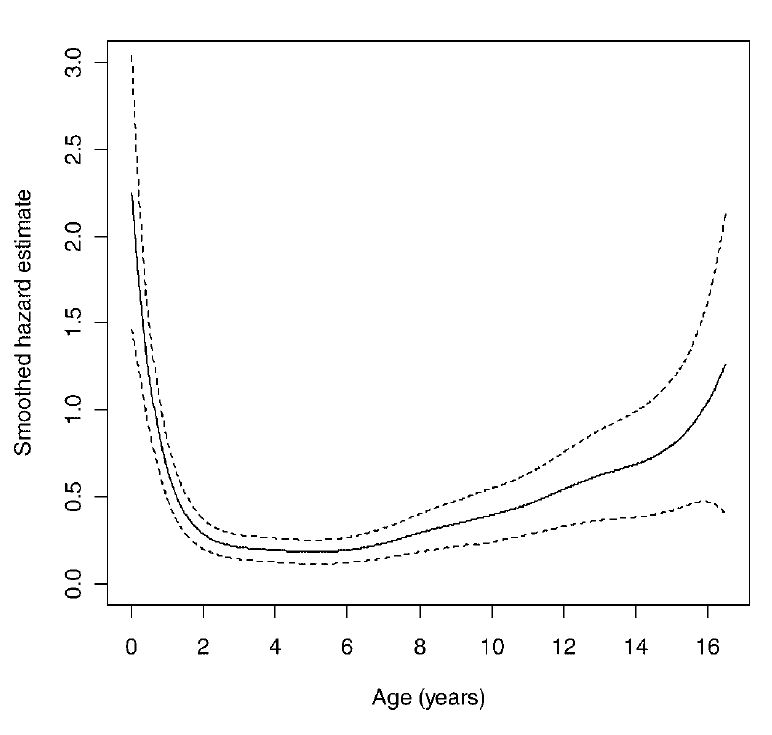

Age-specific Hazard for White-tailed Deer

Linear Models

So far, we have focused on linear models of the form:

\(Y_i = \beta_0 + X_i\beta + \epsilon_i\)

or

\(Y_i = \beta_0 + X_{i,1}\beta_1 + X_{i,2}\beta_2 + \ldots + \epsilon_i\)

The model can be written as a “linear combination” of parameters.

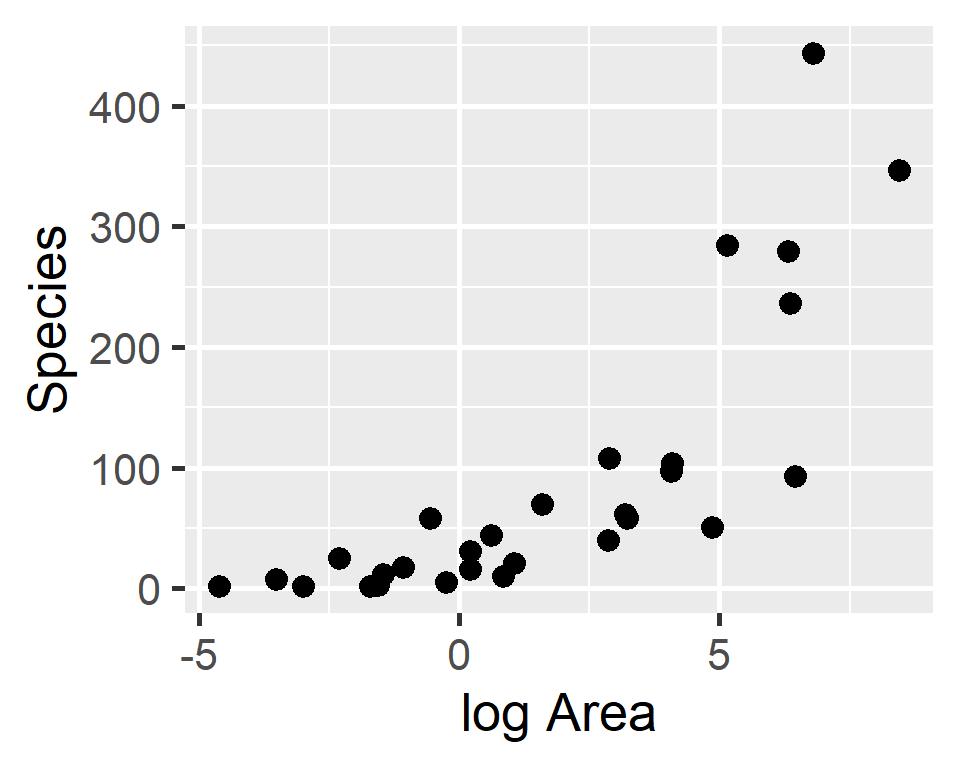

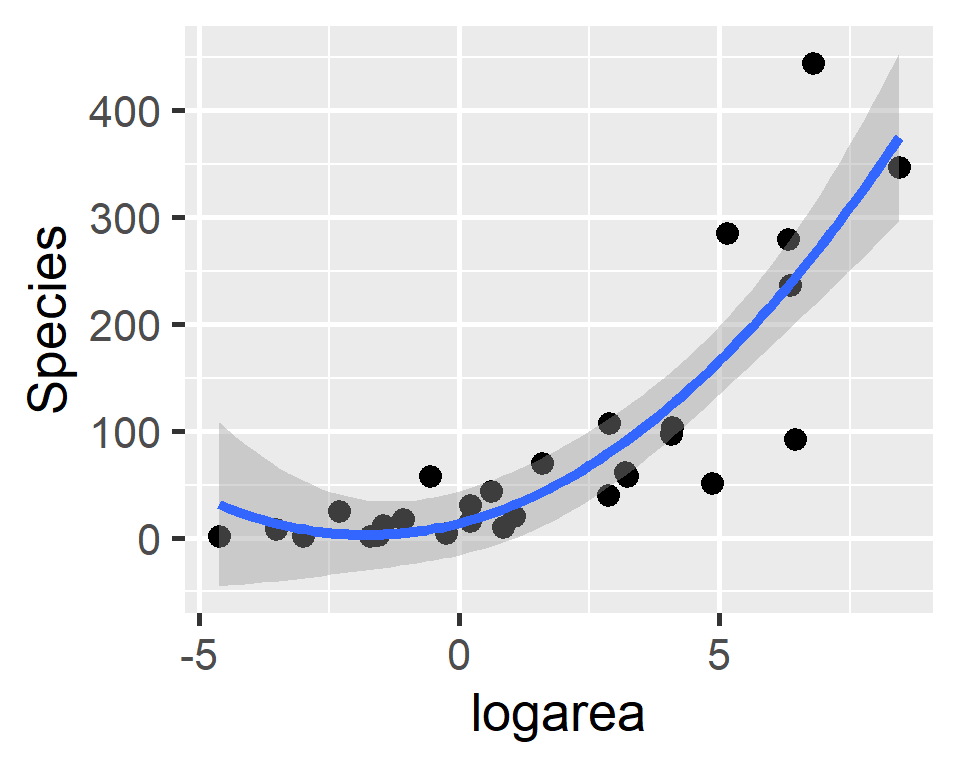

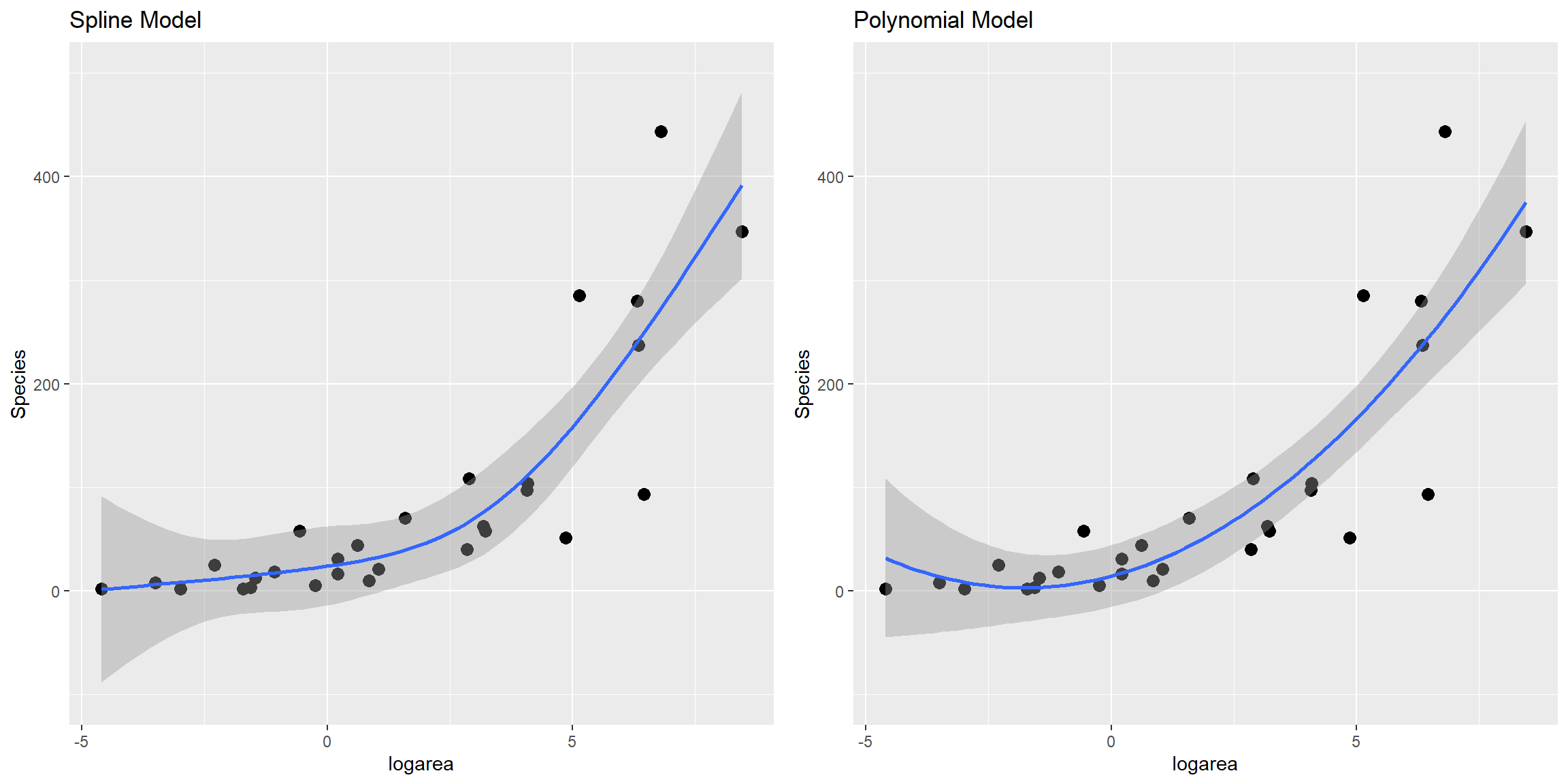

Species-area relationship

Plant species richness for 29 islands in the Galapagos Islands archipelago (Johnson and Raven 1973)

Modeling Non-Linear Relationships

- Polynomials (e.g., poly(age,2) for a quadratic in age)

- Transformations of \(X\) or \(Y\) (e.g., log(\(X\)), \(\sqrt{Y}\), \(exp(X)\)).

- Regression splines

These options still lead to linear models:

\(Y_i = \beta_0 + X_i\beta_1 + X^2_i\beta_2+ \ldots + \epsilon_i\)

\(\sqrt{Y_i} = \beta_0 + log(X_i)\beta_1 + \ldots + \epsilon_i\)

So, we can use all the same tools we’ve learned about (e.g., residual plots, t-tests, F-tests, AIC, etc) [note: try writing out the above models in matrix notation!]

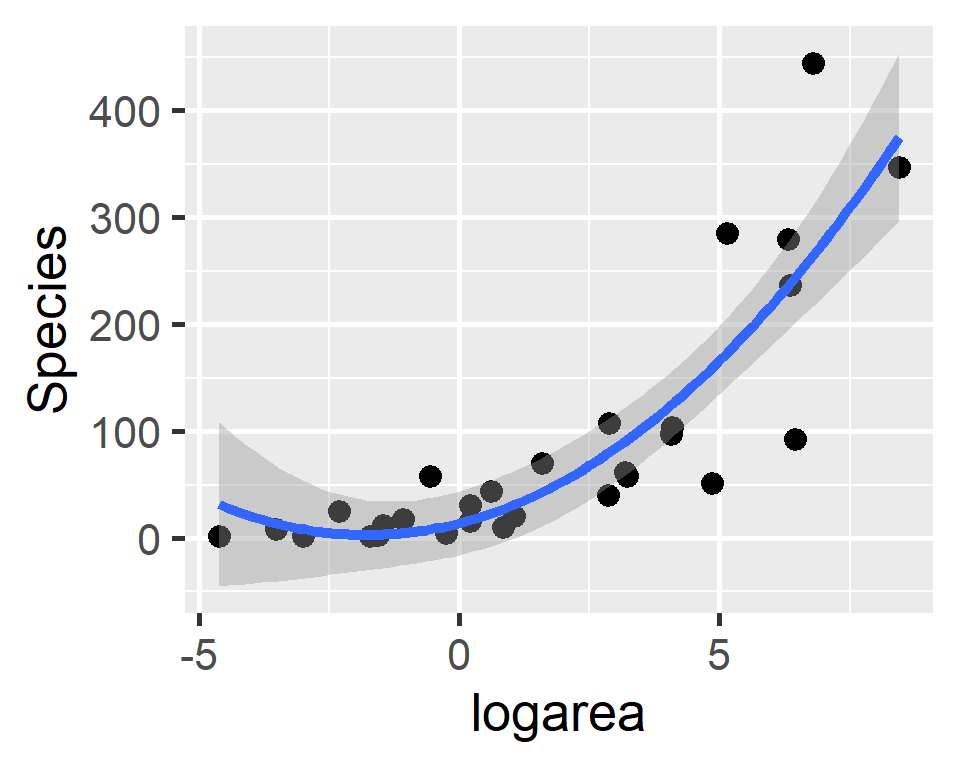

Species-area relationship

Polynomials

gala$logarea.squared<-gala$logarea^2

lm.poly<-lm(Species~ logarea + logarea.squared, data=gala)

summary(lm.poly)

Call:

lm(formula = Species ~ logarea + logarea.squared, data = gala)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-151.009 -27.361 -1.033 20.825 178.805

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 14.1530 14.5607 0.972 0.340010

logarea 12.6226 4.8614 2.596 0.015293 *

logarea.squared 3.5641 0.9445 3.773 0.000842 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 59.88 on 26 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.7528, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7338

F-statistic: 39.6 on 2 and 26 DF, p-value: 1.285e-08Polynomials

Call:

lm(formula = Species ~ poly(logarea, 2, raw = TRUE), data = gala)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-151.009 -27.361 -1.033 20.825 178.805

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 14.1530 14.5607 0.972 0.340010

poly(logarea, 2, raw = TRUE)1 12.6226 4.8614 2.596 0.015293 *

poly(logarea, 2, raw = TRUE)2 3.5641 0.9445 3.773 0.000842 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 59.88 on 26 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.7528, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7338

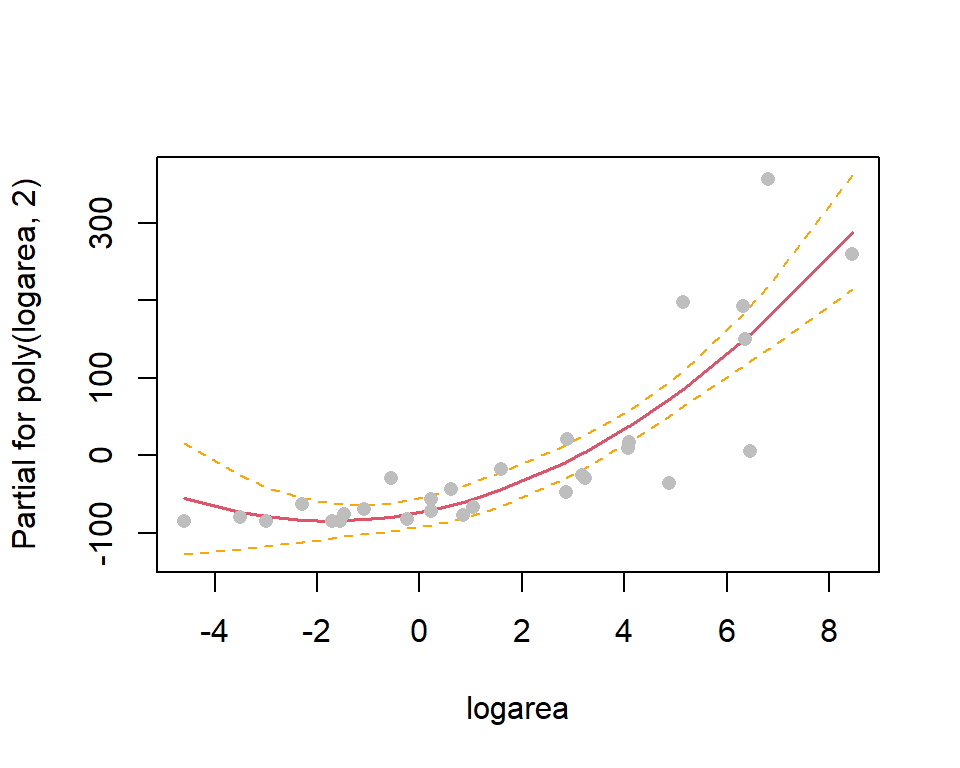

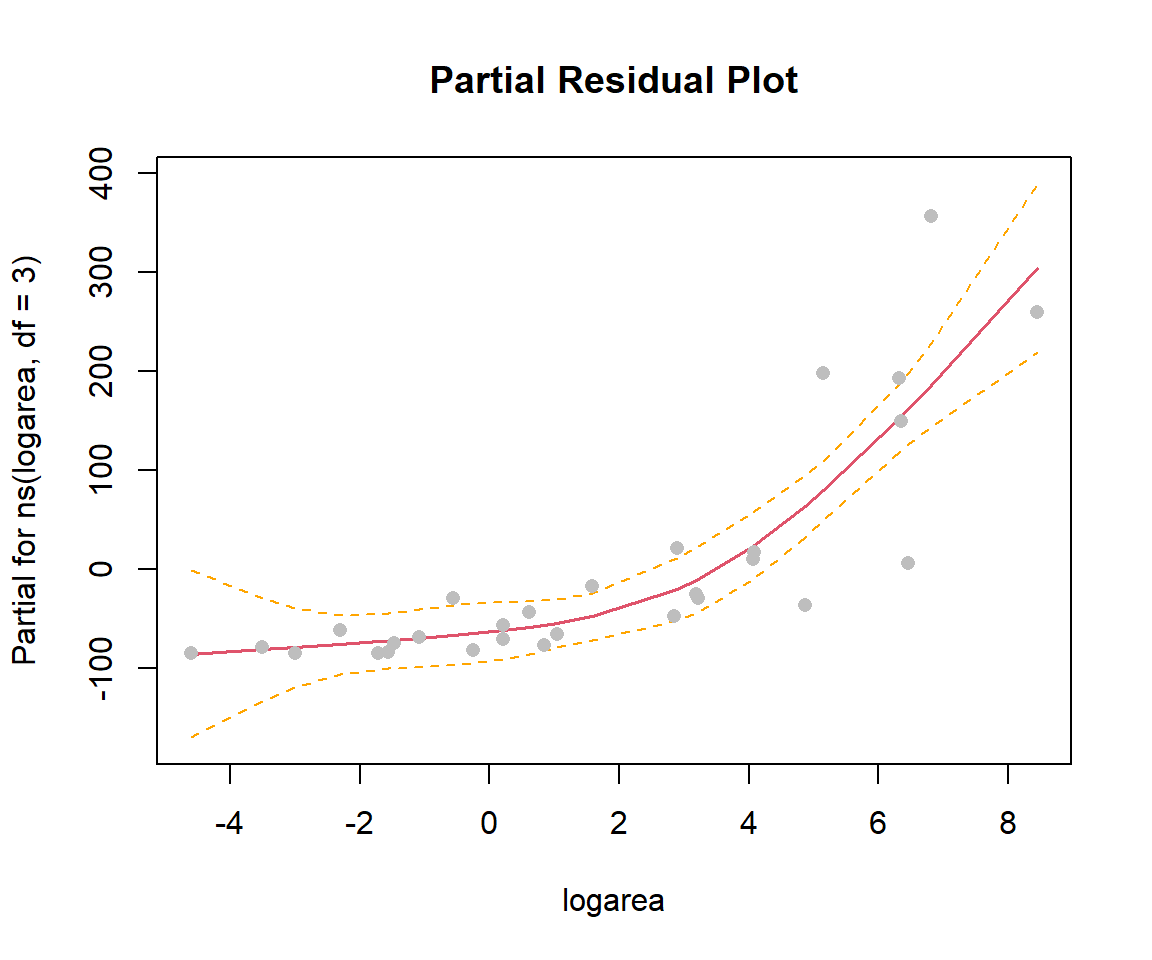

F-statistic: 39.6 on 2 and 26 DF, p-value: 1.285e-08Polynomials: component + residual plot

Hypothesis Testing

Anova Table (Type II tests)

Response: Species

Sum Sq Df F value Pr(>F)

logarea 24175 1 6.7417 0.0152925 *

logarea.squared 51058 1 14.2387 0.0008418 ***

Residuals 93232 26

---

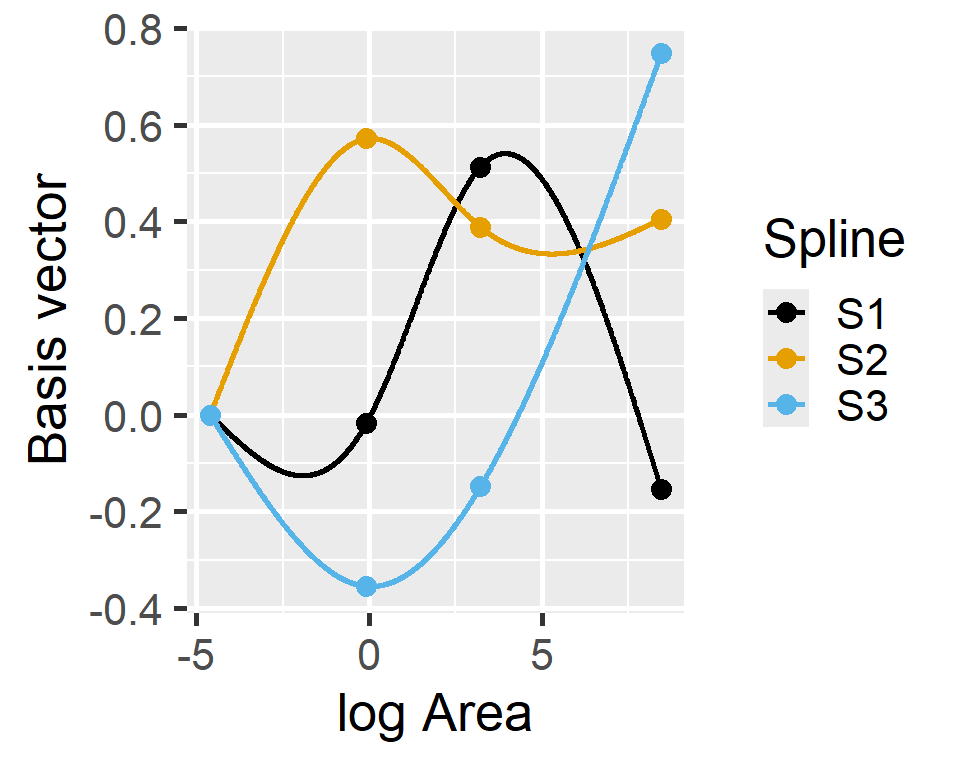

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Basis functions/vectors

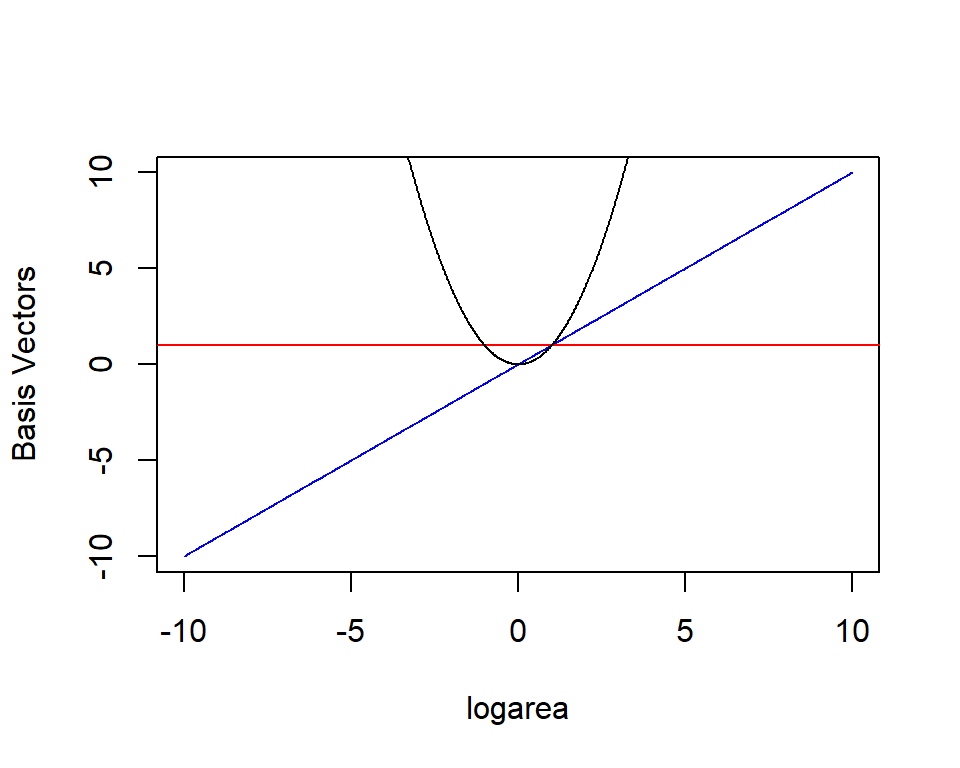

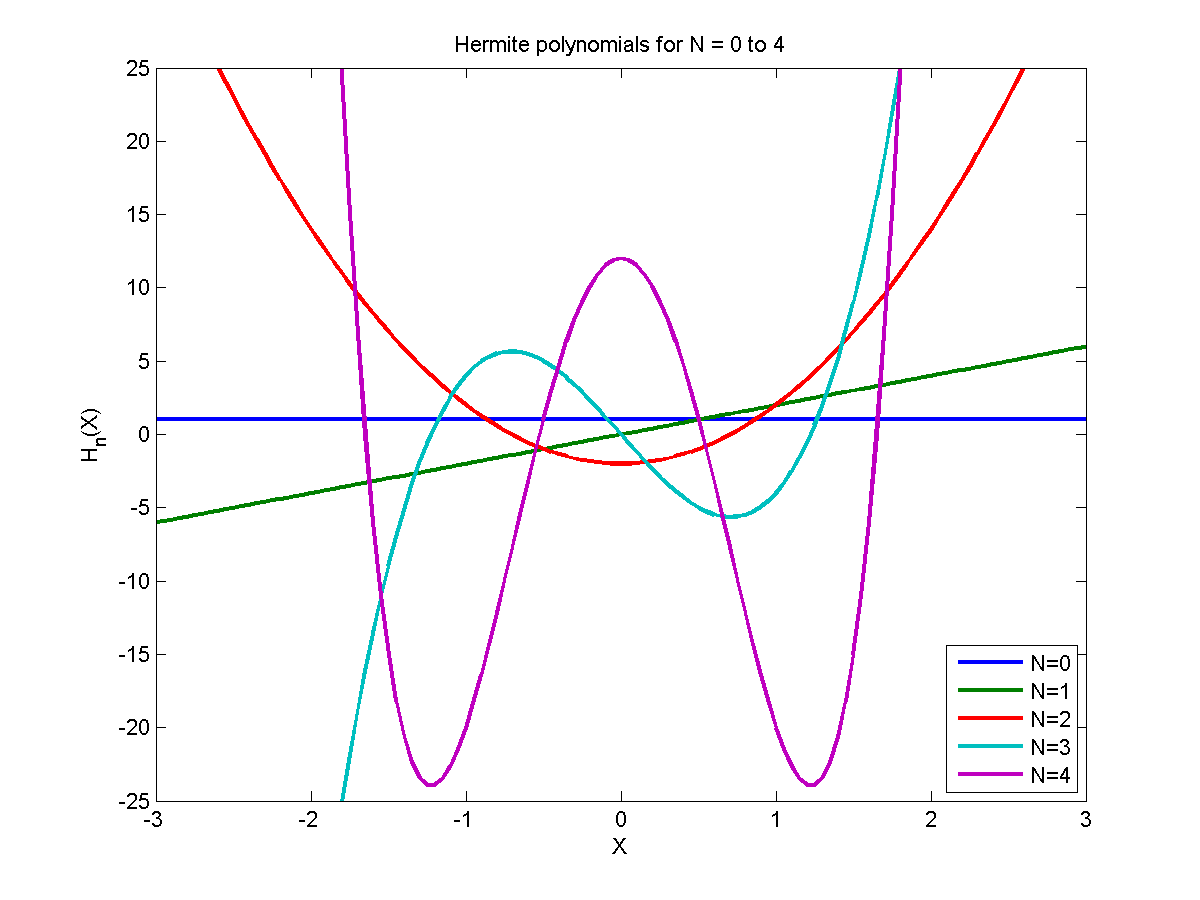

A linear model is a model that is linear in the parameters:

\(Y_i = \sum_{j=1}^P \beta_j b_j(X_i) + \epsilon_i\)

The \(b_j(X_i)\) are called basis functions or basis vectors.

\(Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_2X_i + \beta_3X_i^2 + \ldots + \epsilon_i\)

\(b_j(X_i) = 1, X, X^2, X^3, \ldots\)

Basis functions

\(E[Y_i|X_i] = \beta_01 + \beta_2X_i + \beta_3X_i^2\)

\(E[Y | X]\) is given by a linear combination of a horizontal line (1), a line through the origin (\(X\)), a quadratic centered on the origin (\(X^2\)).

Species-Area relationship

\(Species_i = 14.15 + 12.62X_i + 3.56X^2_i\)

Polynomials

A polynomial of degree D is a function formed by linear combinations of the powers of its argument up to D:

\(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x + \beta_2x^2 + \ldots + \beta_Dx^D\)

Specific polynomials:

- Linear: \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x\)

- Quadratic:: \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x + \beta_2x^2\)

- Cubic: \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x + \beta_2x^2 + \beta_3x^3\)

- Quartic: \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x + \beta_2x^2 + \beta_3x^3+\beta_4x^4\)

- Quintic: \(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x + \beta_2x^2 + \beta_3x^3+\beta_4x^4 + \beta_5x^5\)

Polynomials

The design matrix for a regression model with \(n\) observations and \(p\) predictors is the matrix with \(n\) rows and \(p\) columns such that the value of the \(j^{th}\) predictor for the \(i^{th}\) observation is located in column \(j\) of row \(i\).

Design matrix for a polynomial of degree D

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_1 & x_1^2 & x_1^3 & ... & x_1^D \\ 1 & x_2 & x_2^2 & x_2^3 & ... & x_2^D \\ 1 & x_3 & x_3^2 & x_3^3 & ... & x_3^D \\ & & \vdots & & \\ 1 & x_n & x_n^2 & x_n^3 & ... & x_n^D \\ \end{bmatrix}\)

Polynomials

Orthogonal Polynomials

Standard polynomials can cause numerical issues due to differences in scale:

\(X = 100\) \(x^3 = 1,000,000\)

Centering and scaling \(X\) can help.

Alternatively, we can use “orthogonal polynomials” created using poly(raw=FALSE) (the default). See Section 4.10 in the book.

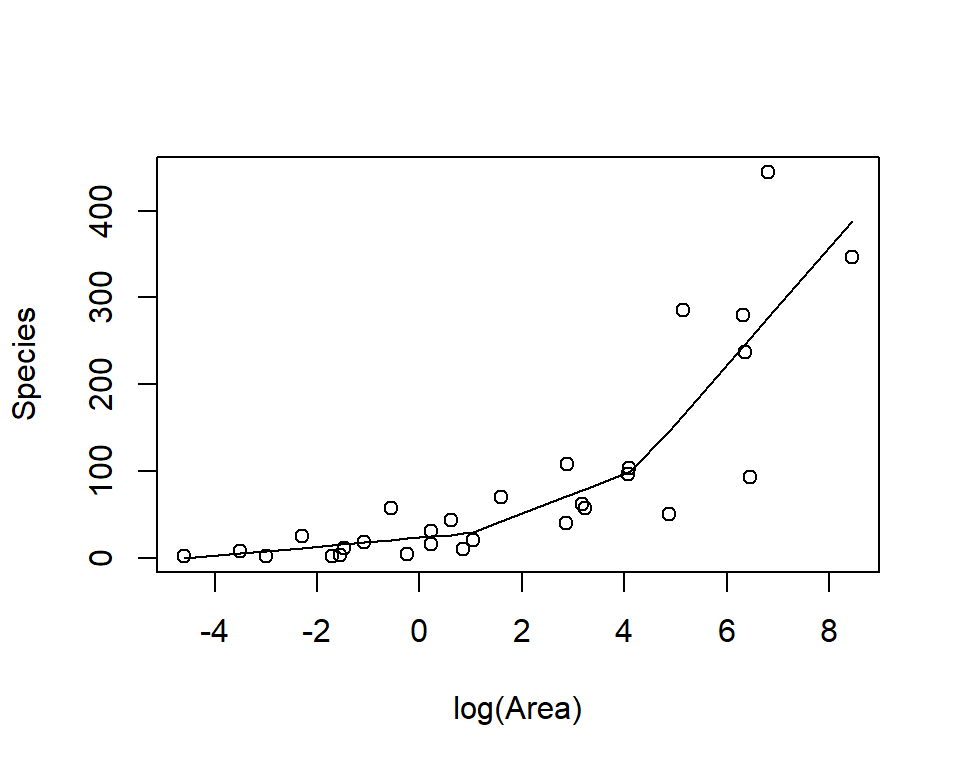

Splines

Species-Area relationship

Linear models are often a good approximation over small ranges of \(x\).

Splines

Splines are piecewise polynomials used in curve fitting.

A linear spline is a continuous function formed by connecting linear segments. The points where the segments connect are called the knots of the spline.

Linear spline with knots at 1 and 4.2

gala$logarea<- log(gala$Area)

gala$logarea.1<- ifelse(gala$logarea<1, 0, gala$logarea-1)

gala$logarea.4.2<- ifelse(gala$logarea<4.2, 0, gala$logarea-4.2)

lm.sp<-lm(Species~logarea+logarea.1+logarea.4.2, data=gala)

summary(lm.sp)

Call:

lm(formula = Species ~ logarea + logarea.1 + logarea.4.2, data = gala)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-160.691 -16.547 -4.209 13.133 166.430

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 23.869 17.384 1.373 0.1819

logarea 5.213 8.956 0.582 0.5658

logarea.1 17.464 18.836 0.927 0.3627

logarea.4.2 44.815 23.156 1.935 0.0643 .

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 58.97 on 25 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.7695, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7418

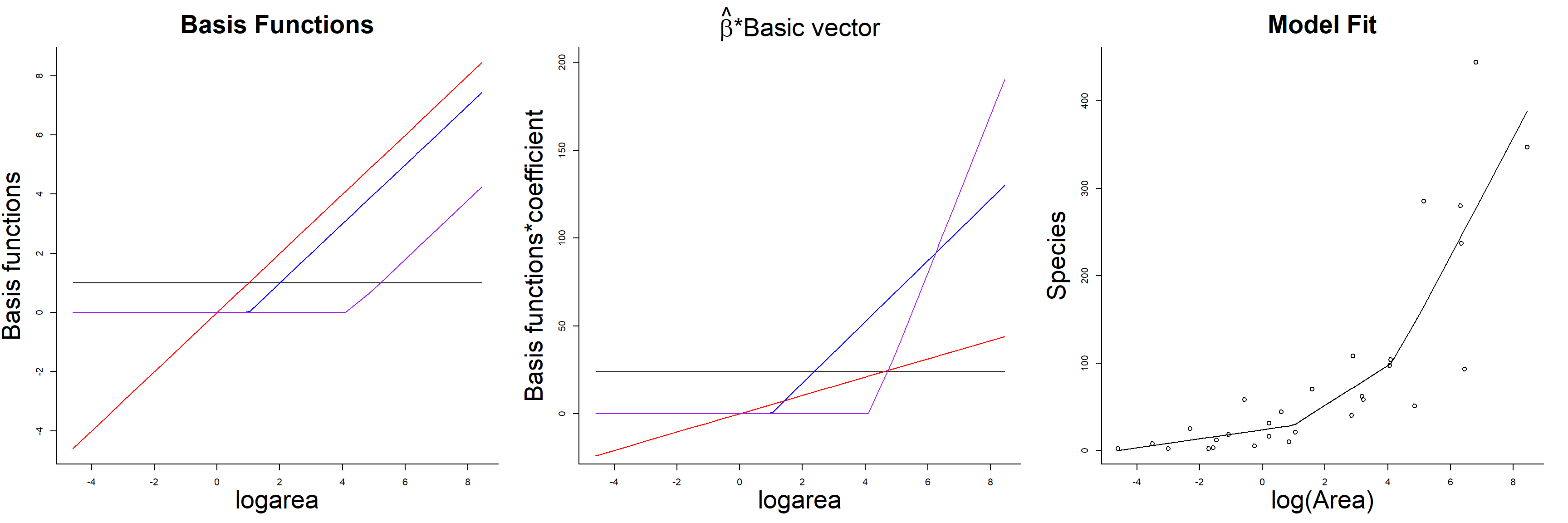

F-statistic: 27.82 on 3 and 25 DF, p-value: 3.934e-08Basis functions

- Left = Basis Functions

- Middle = Basis Functions * regression coefficient

- Right = Fitted Model

Splines

A spline of degree D is a function formed by connecting polynomial segments of degree D so that:

- the function is continuous (no `jumps’)

- the function has D-1 continuous derivatives

- the D\(^{th}\) derivative is constant between knots

Linear splines (D = 1): first derivative is not constant (can go from increasing to decreasing at a knot)

Cubic Regression Splines

Fits a cubic polynomial on segments of the data

D-1 = 2 continuous derivatives everywhere (even at the knot locations)

- the first derivative (tells us if the function is increasing or decreasing) is continuous (even at the knots)

- the second derivative (tell us about curvature) is constant (even at the knots)

- Ensures that the fit is “smooth” at the connections (knot locations)

Truncated Power Basis

The truncated polynomial of degree D associated with a knot \(\xi_k\) is the function which is equal to 0 to the left of \(\xi_k\) and equal to \((x - \xi_k)^D\) to the right of \(\xi_k\).

\((x - \xi_k)^D_+ = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 0 & \mbox{if } x < \xi_k\\ (x - \xi_k)^D & \mbox{if } x \ge \xi_k \end{array} \right.\)

The equation for a spline of degree D with K knots is:

\(y = \beta_0 +\sum_{d=1}^D \beta_Dx^d + \sum_{k=1}^K b_k(x - \xi_k)^D_+\)

Splines

The design matrix for a cubic spline with K knots is the n by 1 + 3 + K matrix with entries:

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_1 & x_1^2 & x_1^3 & (x_1 - \xi_1)^3_+ & ... & (x_1 - \xi_k)^3_+\\ 1 & x_2 & x_2^2 & x_2^3 & (x_2 - \xi_1)^3_+ & ... & (x_2 - \xi_k)^3_+\\ 1 & x_3 & x_3^2 & x_3^3 & (x_3 - \xi_1)^3_+ & ... & (x_3 - \xi_k)^3_+\\ & & \vdots & & \\ 1 & x_n & x_n^2 & x_n^3 & (x_n - \xi_1)^3_+ & ... & (x_n - \xi_k)^3_+\\ \end{bmatrix}\)

Basis functions: Splines

Truncated power basis:

- Easiest to understand, but may run into numerical problems due to scaling issues

Bsplines ( in splines package)

- Numerically more stable than those based on the truncated power basis

- Can be poorly behaved in the tails

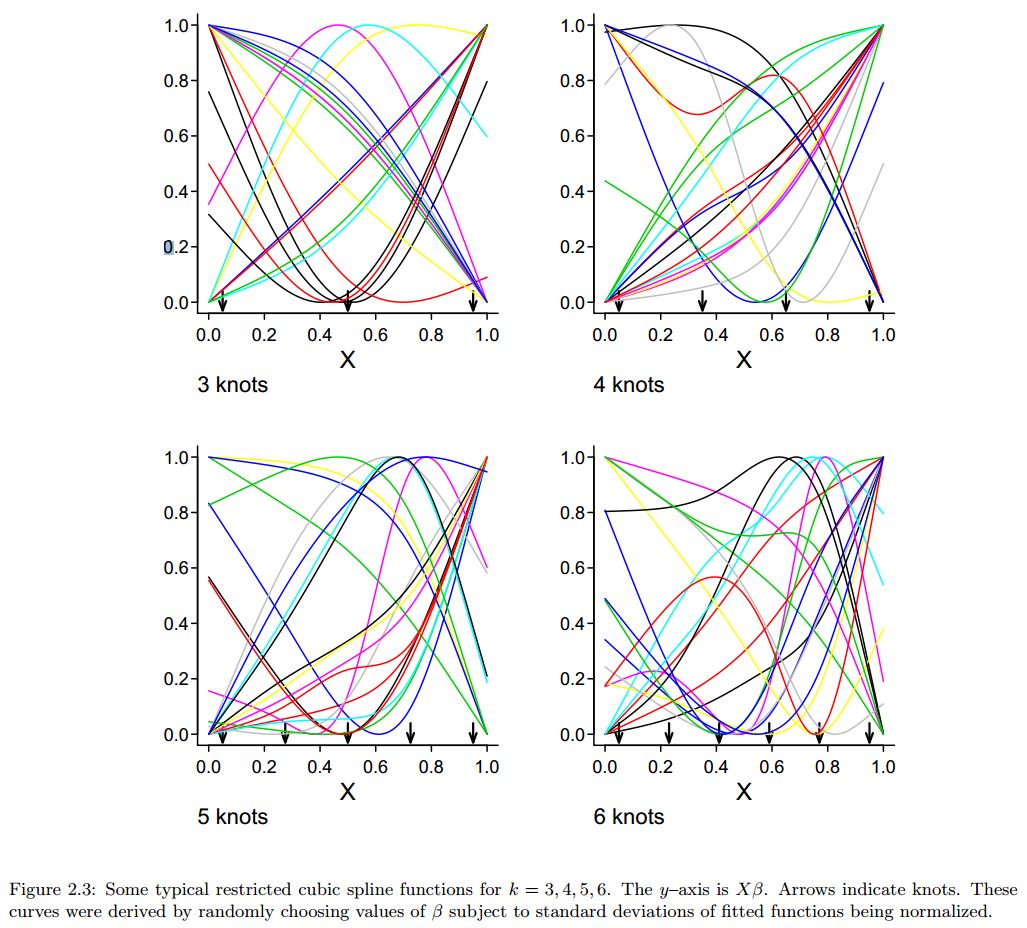

Natural or restricted cubic splines ( in splines package; in rcs package)

- Fit is constrained to be linear before the first knot and after the last knot (these are refered to as )

- Requires fewer model df (number of knots -1 = number of interior knots + 1)

Natural Splines

Call:

lm(formula = Species ~ ns(logarea, df = 3), data = gala)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-156.173 -13.819 -5.998 13.922 170.555

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 1.468 43.542 0.034 0.9734

ns(logarea, df = 3)1 47.790 45.957 1.040 0.3084

ns(logarea, df = 3)2 276.125 102.146 2.703 0.0122 *

ns(logarea, df = 3)3 381.743 45.084 8.467 8.22e-09 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 59.48 on 25 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.7655, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7374

F-statistic: 27.21 on 3 and 25 DF, p-value: 4.859e-08Natural Splines: Basis Vectors

Natural Splines

Code

a <- ggplot(gala, aes(x = logarea, y = Species)) + geom_point(size = 3) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm",

formula = y ~ ns(x, 3),

se = TRUE) + ggtitle("Spline Model") + ylim(c(-100, 500))

b <- ggplot(gala, aes(x = logarea, y = Species)) + geom_point(size = 3) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm",

formula = y ~ poly(x, 2),

se = TRUE) + ggtitle("Polynomial Model")+ ylim(c(-100, 500))

gridExtra::grid.arrange(a, b, ncol = 2)

Natural Splines

Compare fit to that of linear model

df AIC

lmfit 3 335.1547

lm.poly1.raw 4 324.4895

lm.sp 5 324.4646

lm.ns 5 324.9600Any and all approaches fit better than a linear model!

Number of knots and their locations

The shape of a spline can be controlled by carefully choosing the number of knots and their exact locations in order to:

- Allow flexibility where the trend changes quickly, and

- Avoid overfitting where the trend changes little.

Could in principle compare models (e.g., using AIC) that have varying numbers of knots, or different knot locations

- Danger of overfitting, and difficult to account for model-selection uncertainty

Number of knots and their locations

Choose a small number of knots (df), based on how much data you have and how complex you expect the relationship to be a priori

- I’ve found that 2 or 3 internal knots are usually sufficient for small data sets

- Keele (2008), cited in Zuur et al, recommend 3 knots if \(n < 30\) and 5 knots if \(n > 100\)

Choose knot locations based on quantiles (what ns does by default if you do not provide knot locations)

- Models fit with cubic regression splines are usually not too sensitive to knot locations

Span: Splines

Generalized Additive Models

\(E[Y|X] = \beta_0 + f(x_1)\)

where \(f(x_1)\) can be modeled in a variety of ways

- Smoothing splines

- Loess (locally weighted linear regression)

Smoothing or Penalized Splines

Smoothing splines: Use lots of knots, but then attempt to balance overfitting and smoothness.

This balance can be accomplished by controlling the size of the spline coefficients (which reflect changes in the function over different portions of the data range).

See book for short illustration using the mgcv package.

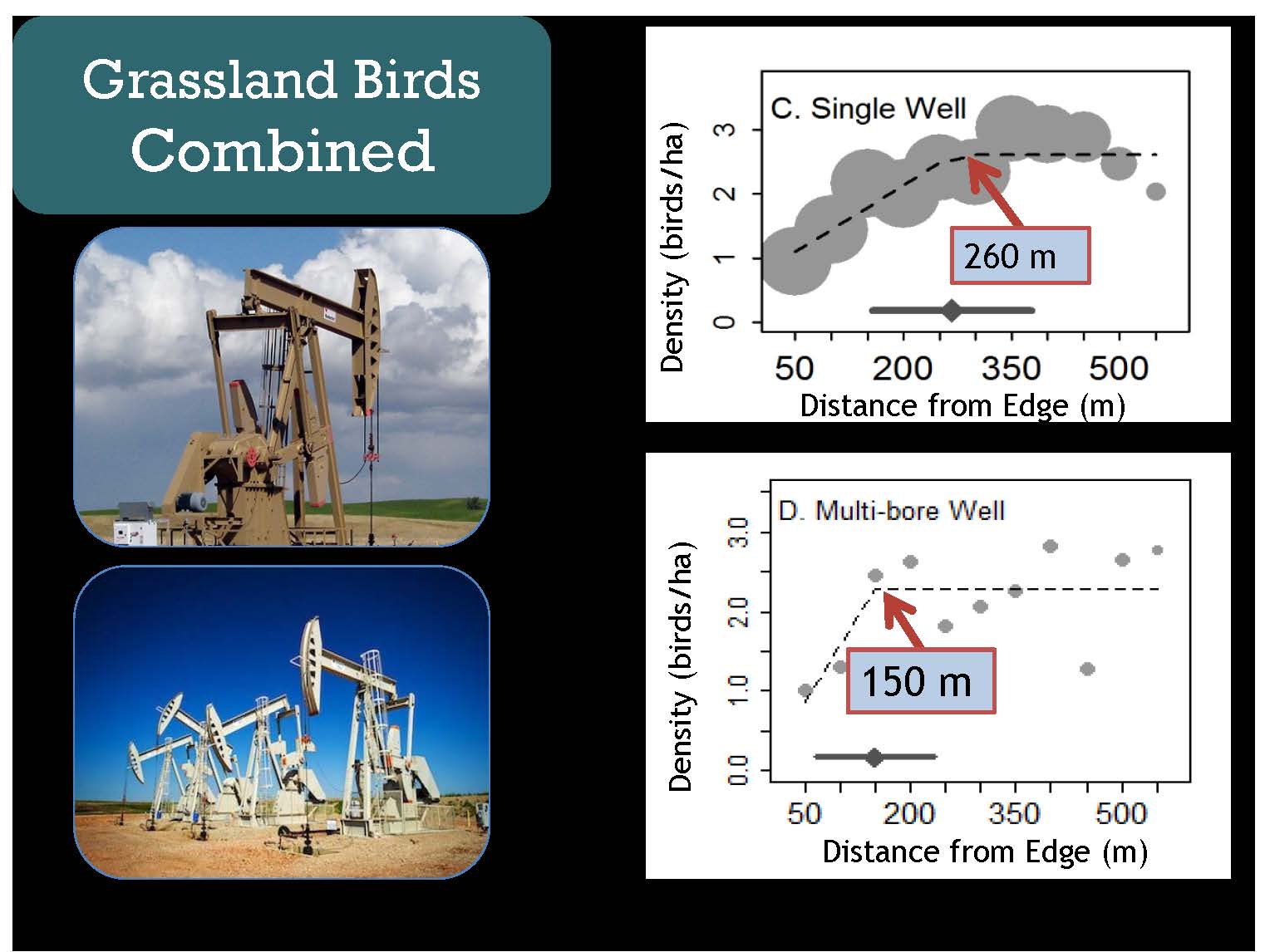

Other considerations

What if you want to allow for multiple non-linear relationships?

ns(x1, 3) + ns(x2, 4)or multiple smoothing splines

- Other basis functions can be used to fit “smooth surfaces” (allowing for interactions between variables)

- tensor splines, thin plate splines, etc…

- Can include interactions (separate smooth for each level of a categorical variable)

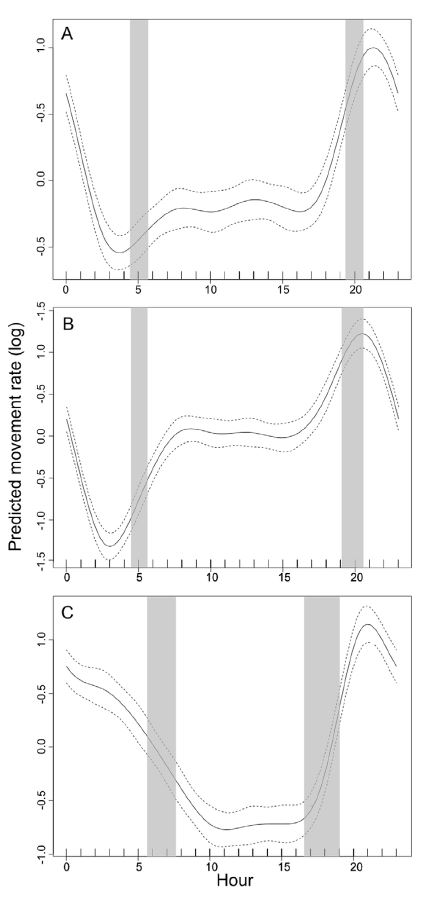

Black Bear Movement and Heart Rates

There are cyclical splines that

ensure ends meet at 0 and 24 hours

(or, Jan 1 and Dec 31).

Non-Linear Models with Mechanistic Basis

\(Y \sim f(x,\beta)\), where \(f(x,\beta)\) may have a strong theoretical motivation.

- Ricker model for stock-recruitment: \(S_{t+1} = S_te^{r(1-\beta S_t)}\)

- Predator prey: \(f(N) = \frac{aN}{1+ahN}\)

We will eventually learn how to fit these models using Maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods.