Correlation, Causation, and Causal networks

Learning objectives

Gain a deeper appreciation for why correlation (or association) is not the same as causation

Discover basic rules that allow one to determine dependencies (correlations) among variables from an assumed causal network

Understand how causal networks can be used to inform the choice of variables to include in a regression model

Causation versus correlation

Knowing what causes what makes a big difference in how we act. If the rooster’s crow causes the sun to rise we could make the night shorter by waking up our rooster earlier and make him crow - say by telling him the latest rooster joke. - Judea Pearl (1936-), computer scientist

Regression

Regression models describe correlations among explanatory (\(x_1, x_2, ...x_k\)) variables and a response variable (\(y\)).

These correlations depend on how the data were collected (e.g., experimental or observation data, the population that was sampled, etc).

Regression coefficients change depending on what other variables are included.

Regression and Causal Mechanisms

Often, we want to interpret models as capturing causal mechanisms so we can say what will happen if we intervene in the system:

- Will taking a daily vitamin improve long-term health?

- Will increasing the pay of teachers or reducing class size boost student performance?

- Will increasing taxes on the rich cause companies to relocate?

- Will we decrease deer population size if we institute an Earn-a-buck regulation?

Counterfactuals

We may also be interested in asking hypothetical questions. What would have happened if…

- A judge may have to decide if a worker’s claim of sex discrimination is legitimate: would the worker have gotten the job if she was a male?

- The National Park Service commissioned a study to ask if fewer birds would have died from collisions had a bridge in Hastings MN been built differently.

These questions involve counterfactuals= something that did not happen, but would have happened if something had been different.

Correlations

Correlations by themselves are not sufficient for answering these questions.

Will taking a daily vitamin improve our long-term health?

People that take vitamins may have better health outcomes, but they may also…

- Exercise more

- Eat healthier

- Drive more cautiously

Interventions: Direct and Indirect Effects

Changing one variable, may lead to changes in others…

If we increase taxes on the rich, can we predict whether businesses will leave the state?

Attractiveness to a business may depend on:

- state taxes

- school system in the state

Increasing taxes may allow a state to invest more in their schools.

- direct effect (negative) due to increased taxes

- indirect effect (positive) through improvement in schools

Predicting the effect of an intervention requires something more complex…

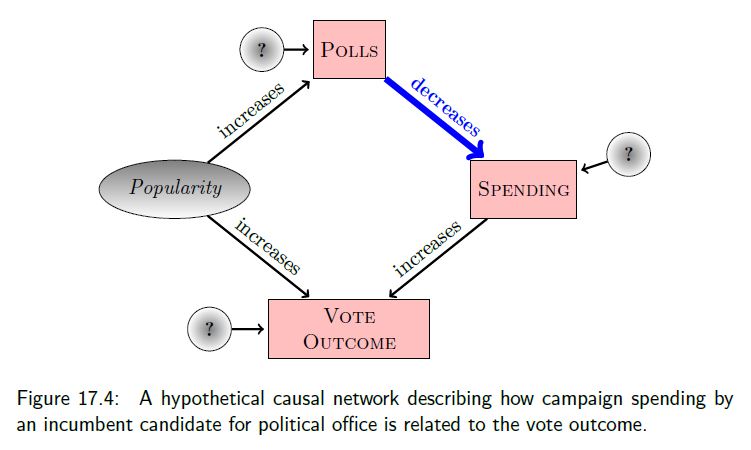

Campaign Spending: Correlation vs. Causation

Campaign spending data from US Congressional elections

- Increased spending by those running for re-election (incumbents) is associated with lower vote percentages

- Does increased spending cause the incumbent to lose votes?

- Does the incumbent spend more when elections are tight?

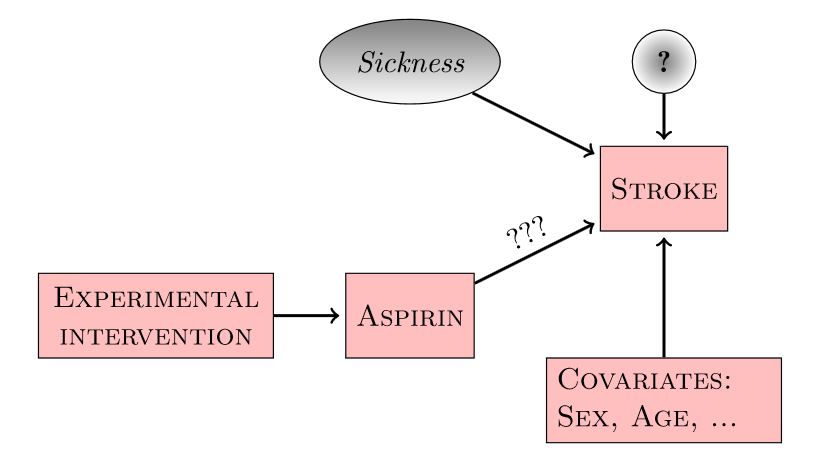

Causal Networks

Causal network= Hypothetical model of how the system works

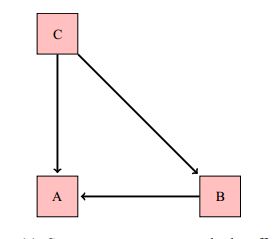

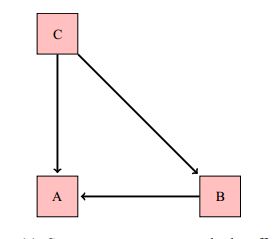

Links and Nodes

Nodes: represent variables or components in a system

- Boxes = observed

- Ellipses = not observed (latent)

- Circles = random noise, suggests something outside of the system influences the variable

Links: connections between nodes

- arrows = causal mechanistic connections

- lines or double arrows = associations (non-causal links)

Circles (things outside of the system) are said to be exogenous.

Shapes with arrows pointing to them are influenced by things inside the system and are said to endogenous.

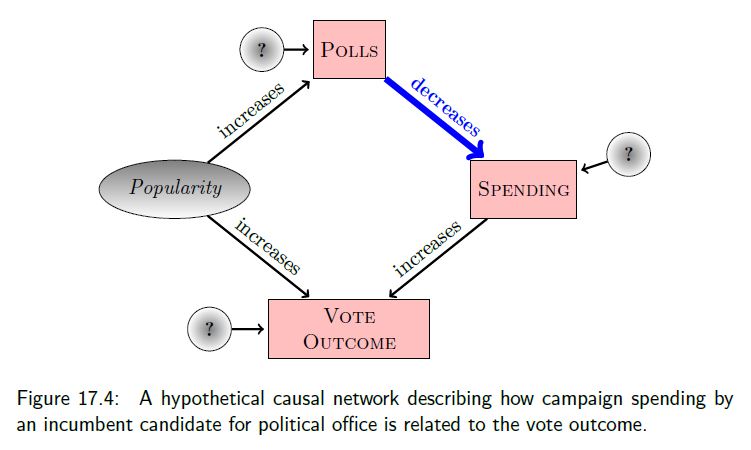

Direct, indirect, and total effects

- A direct effect is one that is represented by a path between two nodes (without consideration of any intermediate nodes): \(C \rightarrow A\)

- An indirect effect is one that connects two nodes, but where we also consider an intermediate node: \(C \rightarrow B \rightarrow A\). \(B\) is a called a mediatorvariable.

- The total effect is the sum of direct and indirect effects

Using Simulation to Explore Campaign Spending

nsamps <- 435 # number of observations

popularity <- runif(nsamps, min=15, max=85)

polls <- popularity + rnorm(nsamps, sd=3)

spending <- 100 - polls + rnorm(nsamps,sd=10)

vote <- 0.75*popularity + 0.25*spending + rnorm(nsamps,sd=5)

votedat<-data.frame(popularity=popularity,

polls=polls, spending=spending, vote=vote)Linear Regression

Call:

lm(formula = vote ~ spending, data = votedat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-32.011 -5.492 0.173 6.193 27.378

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 67.15908 1.04507 64.26 <2e-16 ***

spending -0.35775 0.01932 -18.52 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 9.137 on 433 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.4419, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4406

F-statistic: 342.9 on 1 and 433 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16What happens when we include polls?

Call:

lm(formula = vote ~ spending + polls, data = votedat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-15.2605 -3.8460 0.1036 3.4889 15.5408

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -1.45655 2.55413 -0.57 0.569

spending 0.25910 0.02510 10.32 <2e-16 ***

polls 0.76732 0.02769 27.71 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 5.489 on 432 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.7991, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7982

F-statistic: 859.2 on 2 and 432 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Consider the following DAG:

I’ve simulated data using these assumptions (note interest in nutrition and fishing are not causally connected):

# Set seed of random number generator

set.seed(1040)

# number of students

n <- 5000

# Interest in nutrition sciences

nut <- runif(n, 0, 10)

# Interest in natural resources

nri <- runif(n, 0, 10)

# Number of days fishing

f <- rpois(n, lambda=nri)

# Indicator variable (taking classes on St. Paul campus?)

p <- exp(-5 + 2*nut + 2*nri)/(1+exp(-5 + 2*nut + 2*nri))

z <- rbinom(n, 1, prob=p)

# Create data set

dagdata<-data.frame(nutrition.interest=nut, natresource.interest=nri, fishing=f, stpaulcampus=z)Fishing is unrelated to interest in nutrition

Call:

lm(formula = fishing ~ nutrition.interest, data = dagdata)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-5.0049 -2.9686 -0.0049 2.0640 15.9993

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 4.926949 0.103496 47.60 <2e-16 ***

nutrition.interest 0.007842 0.017838 0.44 0.66

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 3.646 on 4998 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 3.867e-05, Adjusted R-squared: -0.0001614

F-statistic: 0.1933 on 1 and 4998 DF, p-value: 0.6602What if we “adjust” for whether the student is taking classes on the St. Paul campus?

Call:

lm(formula = fishing ~ nutrition.interest + stpaulcampus, data = dagdata)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-5.4351 -2.9100 -0.3057 2.1591 16.1726

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 1.08727 0.26916 4.040 5.44e-05 ***

nutrition.interest -0.06702 0.01810 -3.704 0.000215 ***

stpaulcampus 4.37013 0.28389 15.394 < 2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 3.563 on 4997 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.04531, Adjusted R-squared: 0.04493

F-statistic: 118.6 on 2 and 4997 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Confused?

In the first example, we got the ‘right answer’ when we adjusted for polls.

In the second example, adjusting for whether the student was taking courses on the St. Paul campus created a spurious (negative) correlation between interest in nurtition and fishing.

Should we adjust or not? It depends on one’s hypothetical model of the system (i.e., the causal network)!

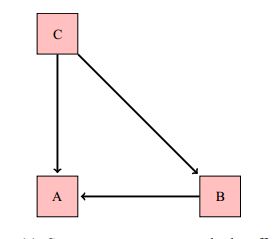

Pathways

A pathway between two nodes is a route between them (may pass through other nodes along the way)

- Correlating pathway follows in the direction of causal links

- Non-correlating pathway one that does not follow in the direction of causal links.

Pathways

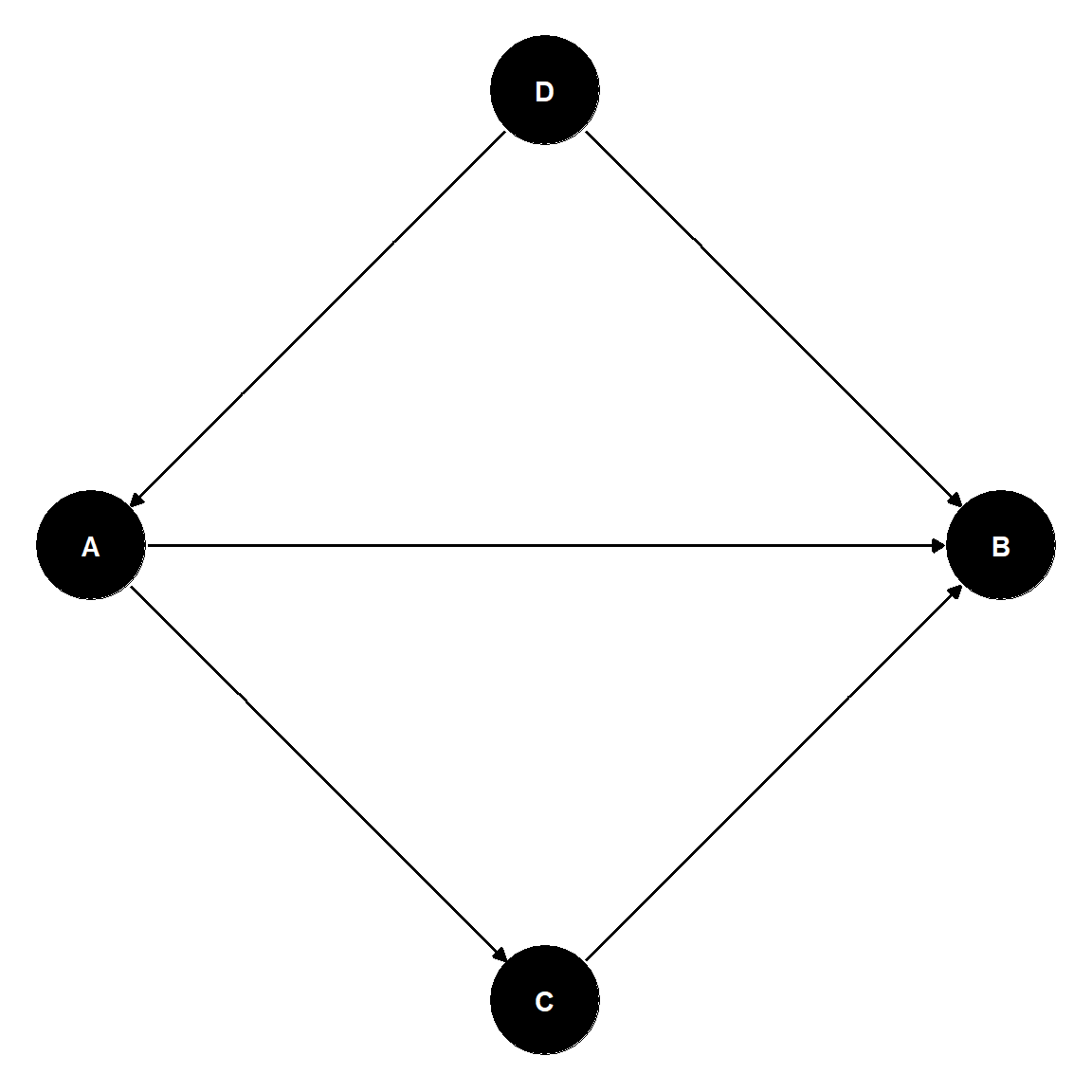

- \(A\) = a response variable

- \(B\) = an explanatory variable

- \(C\) = a covariate

Three Linear pathways:

- Causal mediator: \(A \Leftarrow C \Leftarrow B\)

- Common cause: \(A \Leftarrow C \Rightarrow B\)

- Witness: \(A \Rightarrow C \Leftarrow B\)

Pathways

A pathway between two variables (\(A\) and \(B\)) is correlating if there is a node on the pathway from which you can get to both variables.

- Causal mediator: \(A \Leftarrow C \Leftarrow B\) (correlating)

- Common cause: \(A \Leftarrow C \Rightarrow B\) (correlating)

- Witness: \(A \Rightarrow C \Leftarrow B\) (non-correlating)

What about \(A \Leftarrow C \Leftarrow D \Leftarrow B\)?

Correlating!

Circular Pathways, Correlation

Recurrent (closed loop): \(A \Rightarrow B \Rightarrow C \Rightarrow A\)

Raise questions of “when”…we won’t deal with these

\(A \Leftrightarrow B\) means that there is a non-causal connection between \(A\) and \(B\).

This must be because there is some unobserved variable, \(U\) producing the correlation:

- \(A \Leftarrow U \Rightarrow B\)

Blocking Back Door Pathways

To determine whether to adjust or not, consider these rules and follow the pathways between variables.

- Block correlating pathways: include at least one of the interior nodes on the pathway as a covariate

- DO not unblock non-correlating pathways: exclude all the interior nodes on the pathway; do not include any of them as covariates.

Rules for Deciding When to Include C

- Causal mediator: \(A \Leftarrow C \Leftarrow B\)

Including \(C\) blocks the pathway, which is otherwise open

- Common cause: \(A \Leftarrow C \Rightarrow B\) . . .

Including \(C\) blocks the pathway, which is otherwise open

- Witness: \(A \Rightarrow C \Leftarrow B\)

Including \(C\) opens the pathway, which is otherwise blocked.

Back to Polls

And fishing/nutrition example

Selection Bias

What happens if we only survey students on the St. Paul campus?

Selecting only individuals taking courses on the St. Paul campus has the same effect as adjusting for the variable in the regression.

Selection Bias

Call:

lm(formula = fishing ~ nutrition.interest, data = subset(dagdata,

stpaulcampus == 1))

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-5.4340 -2.9801 -0.3135 2.2062 16.1717

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 5.45626 0.10864 50.224 < 2e-16 ***

nutrition.interest -0.06680 0.01841 -3.629 0.000287 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 3.619 on 4822 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.002724, Adjusted R-squared: 0.002518

F-statistic: 13.17 on 1 and 4822 DF, p-value: 0.000287Some (Summary) Comments on Regression Modeling

- Coefficients may change sign when we include or exclude other explanatory variables

- Whether we should include or exclude a particular variable depends on our hypothetical causal network

- Often useful to explore a few different hypothetical causal models, rather than fit (and average) over many models

Estimates of Direct and Indirect Effects

What if we want to estimate the direct effect of C on A?

Pathways:

\(C \Rightarrow A\) (correlating), and the effect of interest.

\(C \Rightarrow B \Rightarrow A\) (correlating), an indirect effect of \(C\) on \(A\) that is mediated by \(B\)

Include \(B\) to block!

lm(A \(\sim\)C + B)

Estimates of Direct and Indirect Effects

What if we want to estimate the totol effect of C on A?

Pathways:

- \(C \Rightarrow A\) (correlating)

- \(C \Rightarrow B \Rightarrow A\) (correlating)

In this case, we would not want to include B as it would block the second pathway representing an indirect effect of \(C\) on \(A\).

lm(A \(\sim\)C)

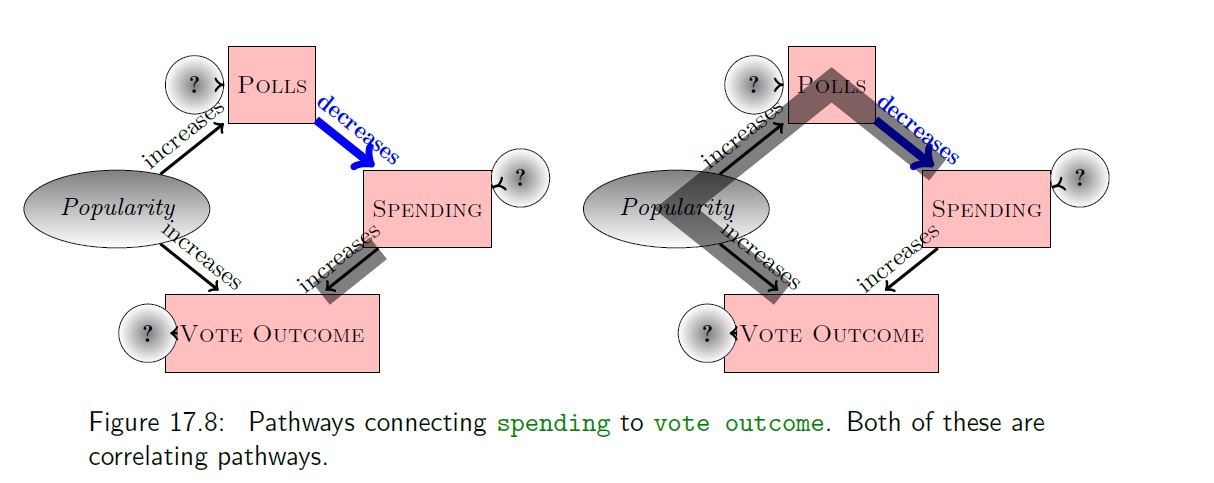

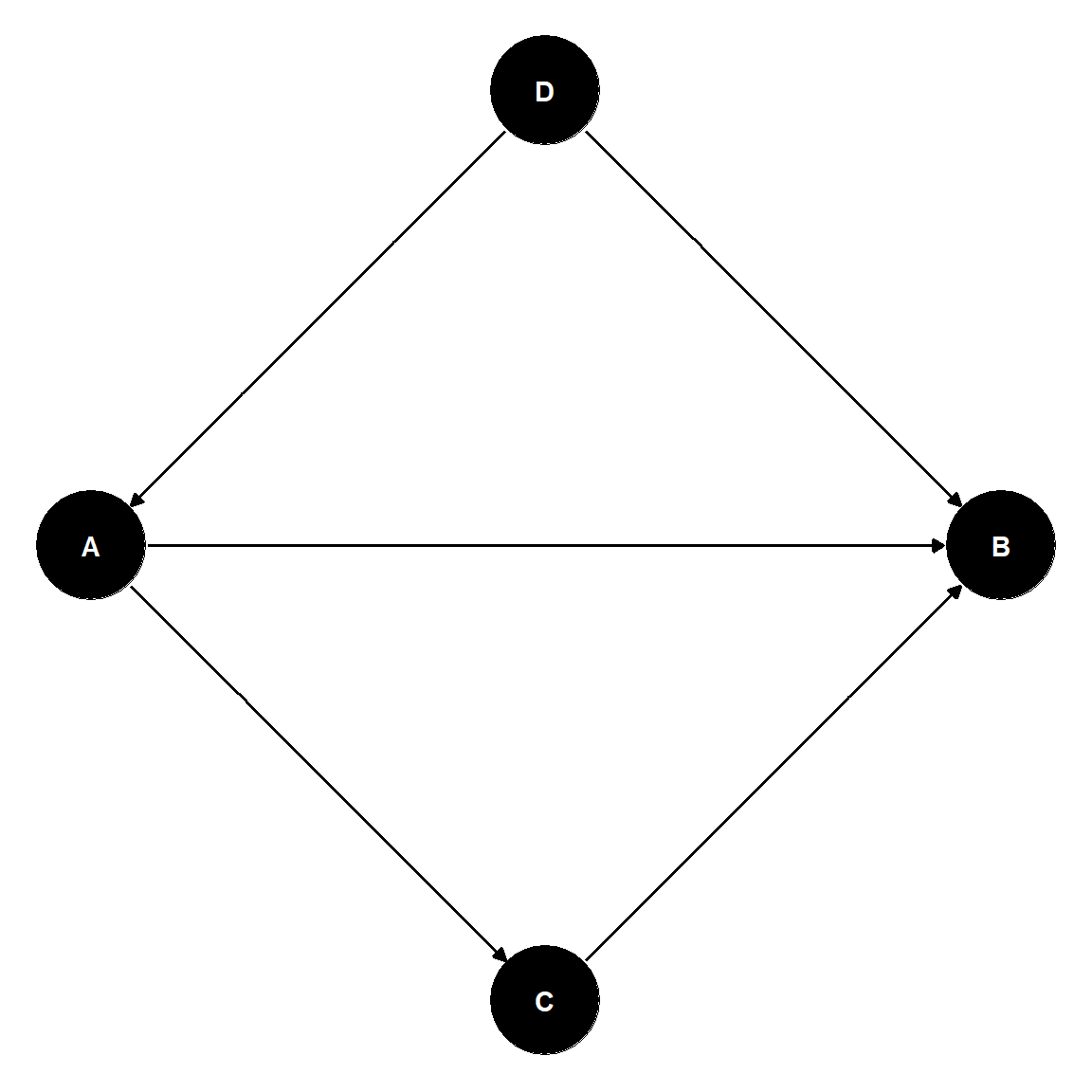

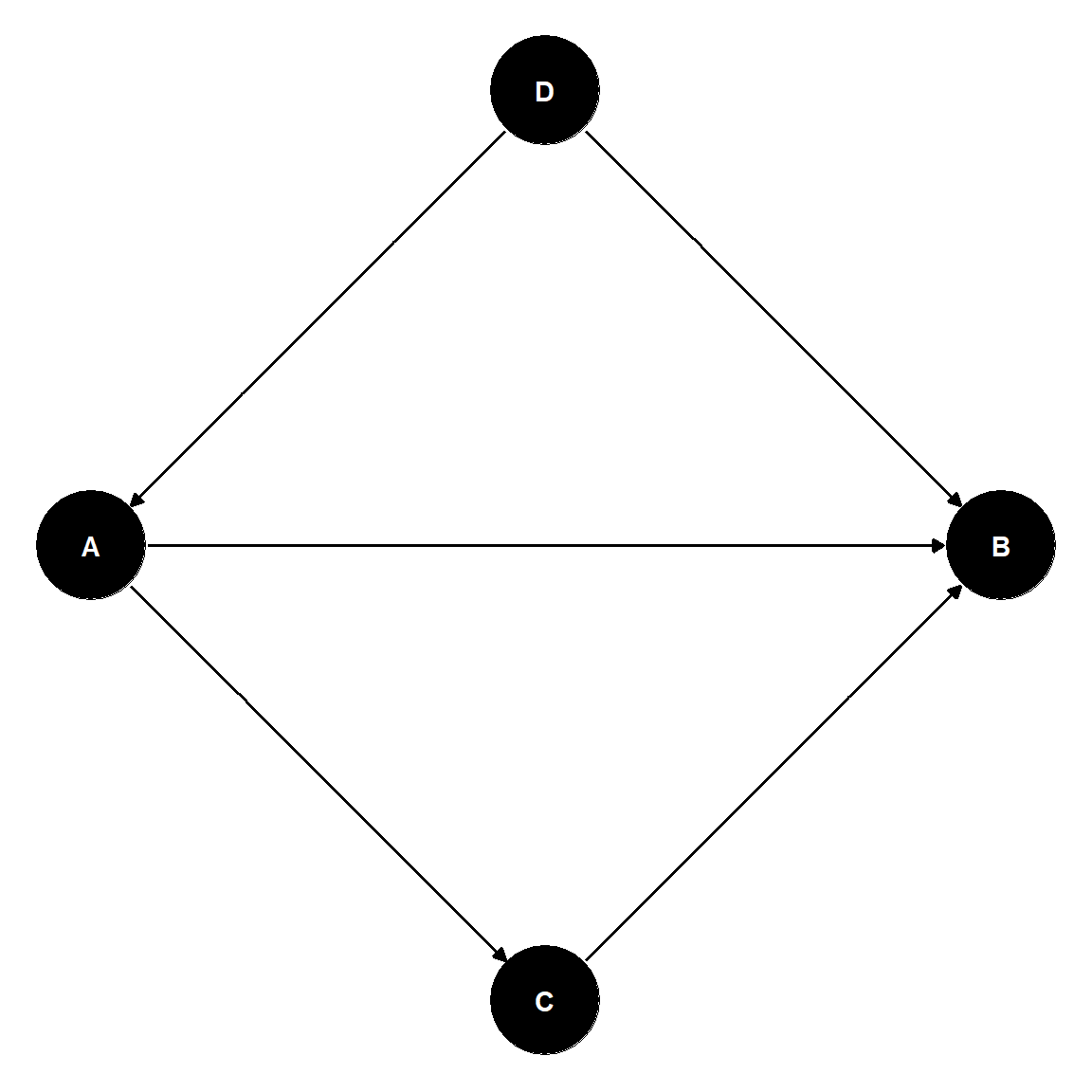

Pathways and Choice of Covariates

Goal: study the direct effect of \(A\) on \(B\).

Pathways and Choice of Covariates

Pathways:

- \(A \Rightarrow B\)

- (correlating), effect of interest.

- \(B \Leftarrow D \Rightarrow A\)

- (correlating) Include D to block!

- \(A \Rightarrow C \Rightarrow B\)

- (correlating) Include \(C\) to block!

lm(B \(\sim\)A + C + D)

To study the total effect of \(A\) on \(B\), we would use:

lm(B \(\sim\)A + D).

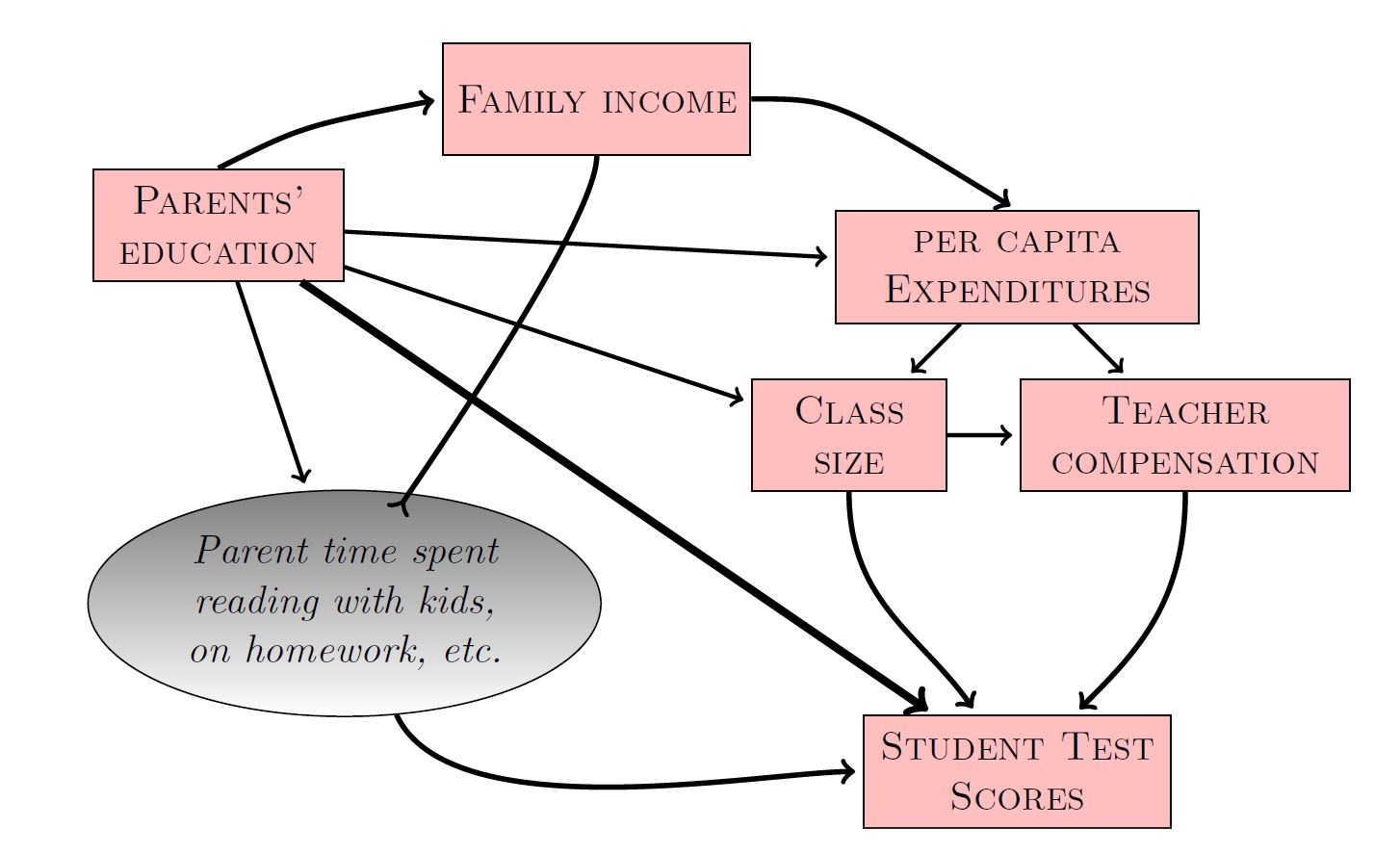

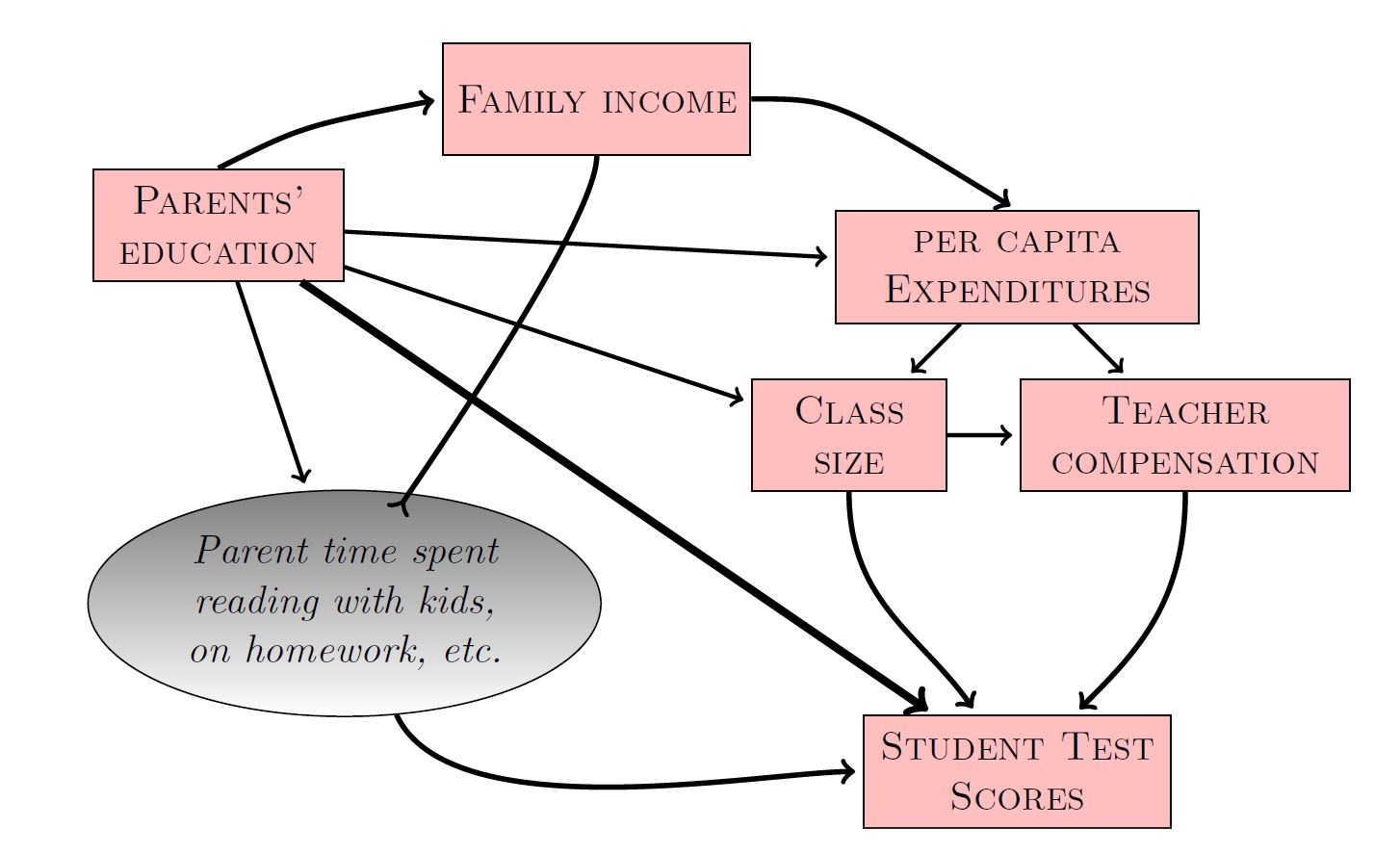

Student Test Scores

Effect of per-captita expenditures on Student Test Scores:

- Include Class Size?

- Include Teacher Compensation?

(No and No)

Per-captia expenditures \(\Rightarrow\) (Class Size, Teacher Compensation) \(\Rightarrow\) Test Scores

Student Test Scores

Include Parents’ Education?

Per-capita expenditures \(\Leftarrow\) Parents’ education \(\Rightarrow\) Test scores

Include Parents’ education to block the path!

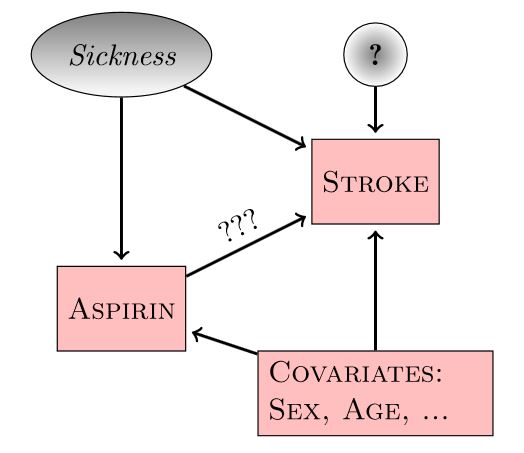

Experiments

How do we measure “sickness” to block the backdoor pathway?

Experiments revisited

Randomly assigning aspirin (treatment) eliminates the connection between Sickness and Aspirin!