The Role of Probability in Regression Models

Learning Objectives

Understand the role of random variables and common statistical distributions in formulating modern statistical regression models.

- Will need to know something about other statistical distributions

- Will need to have an understanding of basic probability theory

- Probability rules and random variables

- Probability mass and probability density functions

- Expected Value and Variance

- How to work with probability distributions in R…

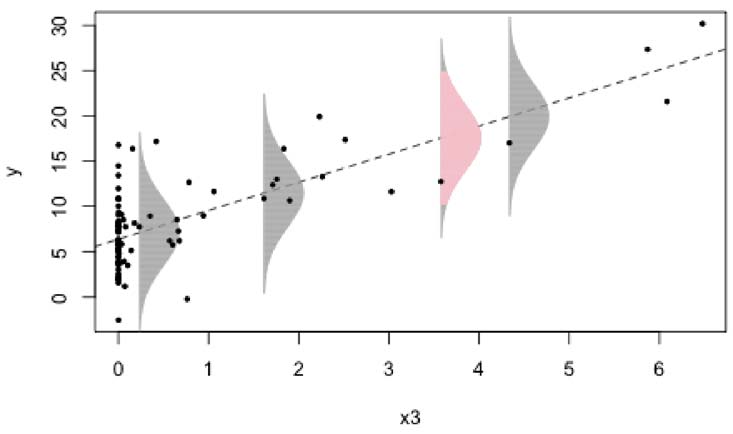

Linear Regression \(y_i = \underbrace{\beta_0 + x_i\beta_1}_\text{Signal} + \underbrace{\epsilon_i}_\text{noise}\)

- Estimated errors, \(\hat{\epsilon}_i\) given by vertical distance between points and the line1

- Find the line that minimizes the errors

Linear Regression

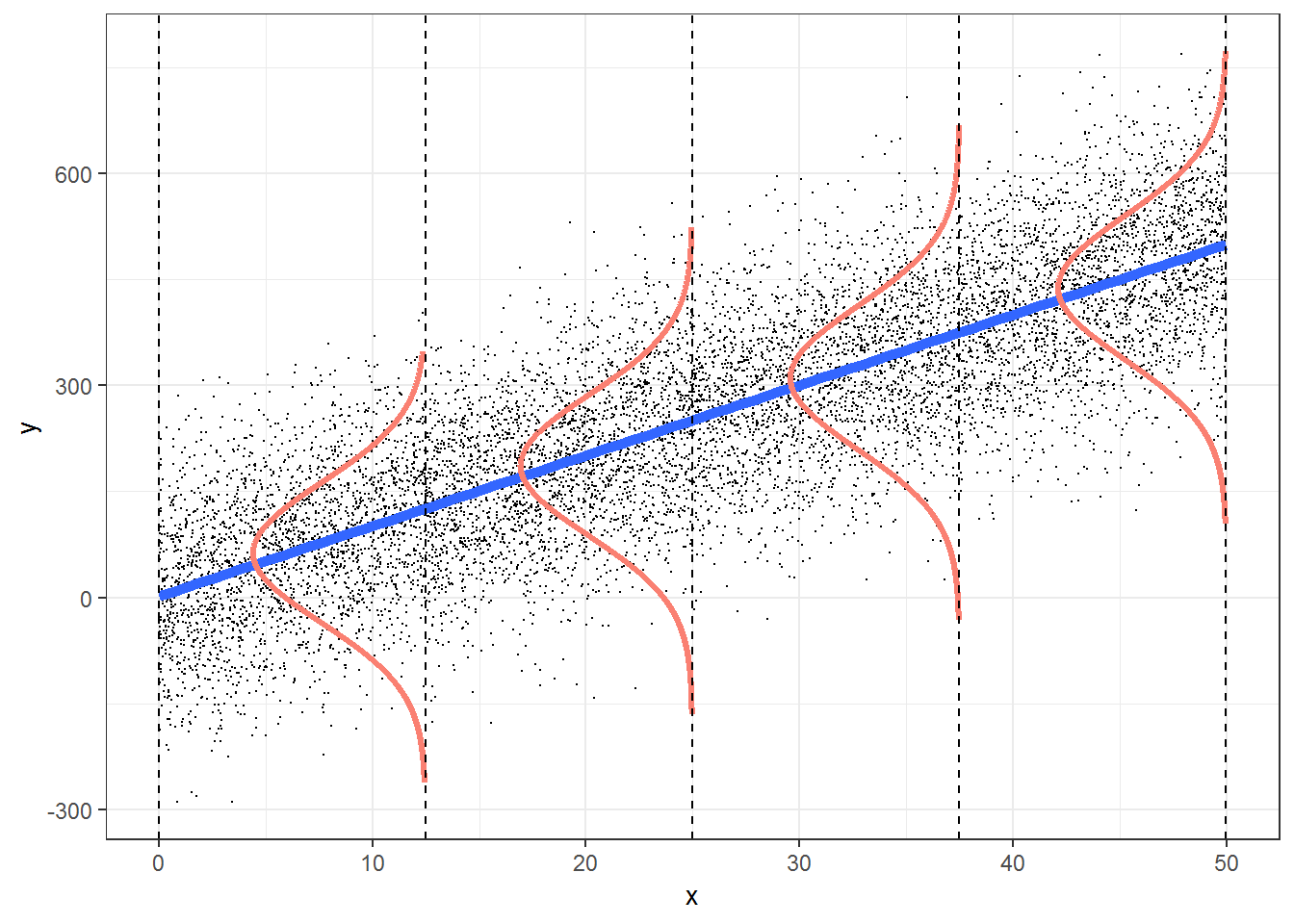

\[Y_i \sim N(\mu_i, \sigma^2)\] \[\mu_i = \beta_0+\beta_1X_i\]

Instead of errors, think about the normal distribution as a data-generating mechanism:

- The line gives the expected (average) value, \(\mu_i\)

- Normal curve describes the variability about this expected value.

Generalizing to other probability distributions

Replace the normal distribution as the data-generating mechanism with another probability distribution, but which one?

It depends on the characteristics of the data

- Does the response variable take on a continuous range of values, only integers, or is it a categorical variable taking on only 1 of 2 values?

Before we learn about different distributions, we need to know a bit more about how we measure probabilities!

Random variables

A random variable is a mapping that takes us from random events to random numbers.

Discrete Random Variables can take on a finite (or countably infinite1) set of possible values.

- Number of birds seen on a plot {0, 1, 2, …}

- Whether or not a moose calf survives its first year {yes, no} \(\rightarrow\) {0, 1}

Continuous Random variables take on random values within some interval.

- T = the age at which a randomly selected white-tailed deer dies (0, \(\infty\))

- W = Mercury level (ppm) in a randomly chosen walleye from Lake Mille Lacs [0, \(\infty\))

- (x, y) such that x,y falls within the continental US

Discrete random variables

Probability Mass Function

A probability mass function, \(p(x)\), assigns a probability to each value that a discrete random variable, \(X\), can take on.

- Flip a coin twice, with the following possible random events: {HH, TH, HT, TT}

- Let \(X\) be a discrete random variable that counts the number of heads (0, 1, or 2).

Probability mass function:

| x | p(x) |

| 0 | 1/4 |

| 1 | 1/2 |

| 2 | 1/4 |

Note: for any probability mass function \(\sum p(x) = 1\)

Bernoulli Distribution

Many categorical response variables can take on only one of two values (dead or alive, migrated or not, etc.)

A Bernoulli random variable, \(X\), maps the two possibilities to the numbers {0, 1} with probabilities \(1-p\) and \(p\), respectively.

| x | p(x) |

| 0 | 1-p |

| 1 | p |

\[X \sim Bernoulli(p)\]

Probability mass function:

\[p(x) = P(X = x) = p^x(1-p)^{1-x}\]

Mean of a Discrete Random Variable

The mean for a discrete random variable with probability function, p(x), is given by:

\[E[X] = \sum_{x} xp(x)\]

\[X \sim Bernoulli(p)\]

| x | p(x) |

| 0 | 1-p |

| 1 | p |

- \(E[X] = \sum\limits_{x\in (0,1)} xp(x) =\) \(0(1-p) + 1p = p\)

Variance and Standard Deviation

The variance for a discrete random variable with probability function, p(x), and mean \(E[x]\) is given by:

\(Var(X) = E(X-E(X))^2 = \sum \limits_{x} (x-E[x])^2p(x) = E[x^2]-(E[x])^2\)

The standard deviation is \(\sigma=\sqrt{Var(x)}\)

\[X \sim Bernoulli(p)\]

| x | p(x) |

| 0 | 1-p |

| 1 | p |

- \(Var[X] = \sum\limits_{x\in (0,1)} (x-E[x])^2p(x)\) \(=(0-p)^2(1-p) + (1-p)^2p = p(1-p)\)

Continuous random variables

Probability Density Function f(x)

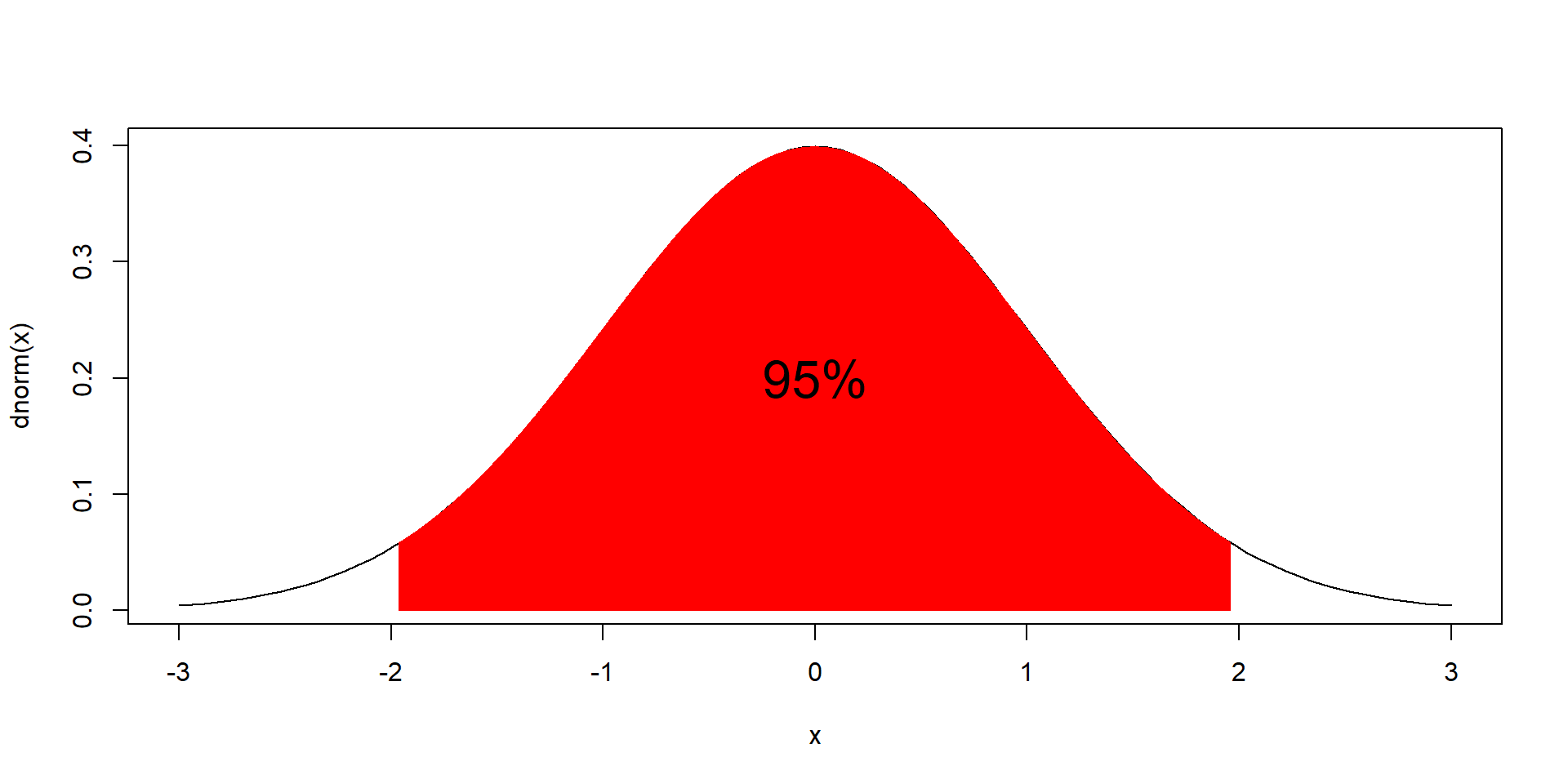

\[X \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2)\]

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}\exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right)\]

Probabilities are measured in terms of areas under the curve, \(f(x)\):

\[P(-1.96 < X < 1.96) = \int_{-1.96}^{1.96} f(x)dx = 0.95\]

- Probability of any point, P\((X = x)\) = 0

- P(a \(\le X \le\) b) = P(a \(< X <\) b)

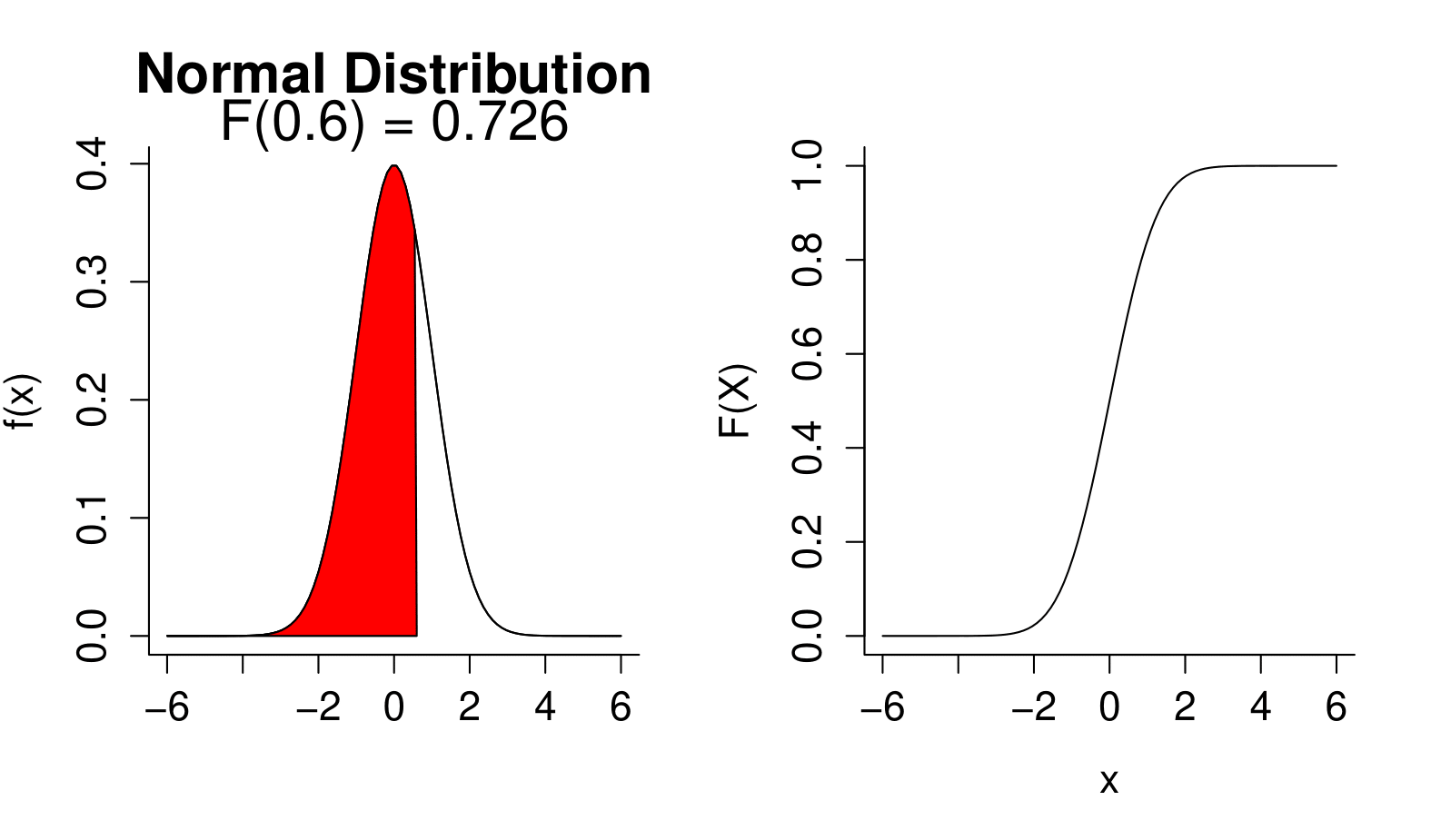

Cumulative Density Function F(x)

Probability density function, \(f(X)\)

Cumulative distribution function, \(F(X) = P(X \le x)= \int_{-\infty}^{x}f(x)dx\)

- Unlike probabilities f(x) can be greater than 1

- \(\int f(x)dx = 1\) (area under the curve is one)

- \(F(x)\) goes from 0 to 1

E[X], Var[X], Continuous random variables

Replace sums with integrals!

Mean: \(E[X] = \mu = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}xf(x)dx\)

Variance: \(Var(X) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}(x-E[X])^2f(x)dx\)

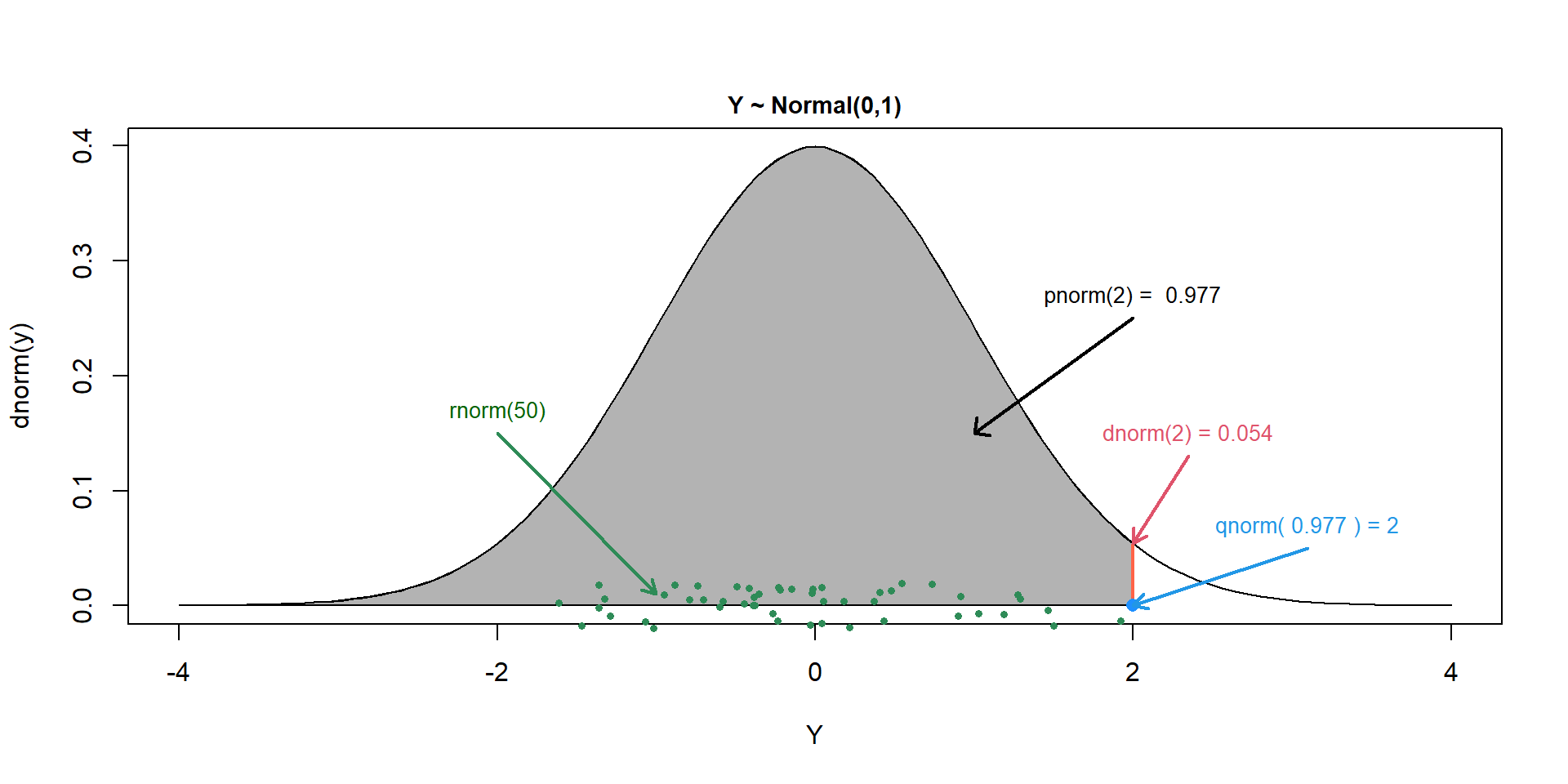

Distributions in R

For each probability distribution in R, there are 4 basic probability functions, starting with either - d, p, q, or r:

d is for “density” and returns the value of f(x) - probability density function (continuous distributions) - probability mass function (discrete distributions).

p is for “probability”; returns a value of F(x), cumulative distribution function.

q is for “quantile”; returns a value from the inverse of F(X); also know as the quantile function.

r is for “random”; generates a random value from the given distribution.

Functions in R

Use this graph, and R help functions if necessary, to complete Exercise 9.1 in the companion book.

Normal Distribution \(X \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2)\)

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}\exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right)\]

Parameters:

- \(\mu = E[X]\)

- \(\sigma^2 = Var[X]\)

Characteristics:

- Mean and variance are independent (knowing one tells us nothing about the other)…this is unique!

\(X\) can take on any value (i.e., the range goes from \(-\infty\) to \(\infty\)) …

R normal functions: dnorm, pnorm, qnorm, rnorm.

JAGS: dnorm

Why is the Normal Distribution so Popular

- Central limit theorem (as \(n\) gets large, \(\bar{x}, \sum x\)) become normally distributed

- Model for measurements that are influenced by a large number of factors that act in an additive way

Other notes:

- In JAGS, WinBugs, specified in terms of precision \(\tau = 1/\sigma^2\)

- In R, specified in terms of \(\sigma\) not \(\sigma^2\).

- Often used for priors (Bayesian analysis) to express ignorance (e.g., N(0,100) for regression parameters).

log-normal Distribution: \(X \sim\) Lognormal\((\mu,\sigma)\)

- \(X\) has a log-normal distribution of if \(\log(X) \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2)\)

- \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are the mean and variance of log(\(X\)) not \(X\)

- Range: > 0

- R: dlnorm, plnorm, qlnorm, rlnorm with parameters and

- \(E[X] = \exp(\mu+ 1/2 \sigma^2)\)

- \(Var(X)= \exp(2\mu + \sigma^2)(\exp(\sigma^2)-1)\)

- \(Var(X) = kE[X]^2\)

Motivation for log-normal

CLT: if we sum a lot of independent things, then we get a normal distribution.

If we multiply a lot of independent things, we get a log-normal distribution, since:

\[log(X_1X_2\cdots X_n) = log(X_1)+log(X_2)+\ldots log(X_n)\]

Possible examples in biology? Population dynamic models

Lognormal Distribution

Explore briefly in R:

Compare to the expressions for the mean and variance as a function of (\(\mu, \sigma\)):

- \(E[X] = \exp(\mu+ 1/2 \sigma^2)\)

- \(Var(X)= \exp(2\mu + \sigma^2)(\exp(\sigma^2)-1)\)

Bernoulli Distribution:

\[X \sim Bernoulli(p)\]

\[f(x) = P(X = x) = p^X(1-p)^{1-x}\]

- One parameter, \(p\), the probability of ‘success’ = \(P(X=1)\)

- \(0 \le p \le 1\)

- \(E[X] = p\)

- \(Var[X] = p(1-p)\)

- JAGS and WinBugs: dbern

- R has only Binomial distribution (next)

Binomial random variable: \(X \sim\) Binomial\((n,p)\)

A binomial random variable counts the the number of “successes” (any outcome of interest) in a sequence of trials where

- The number of trials, n, is fixed in advance

- The probability of success, p, is the same on each trial

- Successive trials are independent of each other

Formally, a binomial random variable arises from a sum of independent Bernoulli random variables, each with parameter, \(p\):

\[Y = X_1+X_2+\ldots X_n\]

Binomial Probability Function

For a binomial random variable with n trials and probability of success p on each trial, the probability of exactly k successes in the n trials is:

\(P(x = k) ={n \choose k}p^k(1-p)^{n-k}\)

\({n \choose k} = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}\) with \(n!\) = \(n(n-1)(n-2) \cdots (2)1\)

- \(E[X] = np\)

- \(Var(X) = np(1-p)\)

- In R: dbinom, pbinom,qbinom,rbinom

size= \(n\) andprob= \(p\) when using these functions.

Free Throws

Raymond Felton’s free throw percentage during the 2004-2005 season at North Carolina was 70%. If we assume successive attempts are independent, what is the probability that he would hit at least 4 out of 6 free throws in 2005 Championship Game (he hit 5)?

\(P(X \ge 4) = P(X=4) + P(X=5) + P(X=6)\)

\(= {6 \choose 4}0.7^{4}0.3^2 + {6 \choose 5}0.7^{5}0.3^1 + 0.7^{6}\)

Multinomial Distribution

\[X \sim Multinomial(n, p_1, p_2, \ldots, p_k)\]

- Records the number of events falling into each of \(k\) different categories out of \(n\) trials.

- Parameters: \(p_1, p_2, \ldots, p_k\) (associated with each category)

- \(p_k = 1-\sum_{i-1}^{k-1}p_i\)

- Generalizes the binomial to more than 2 (unordered) categories

- R: dmultinom, pmultinom, qmultinom, rmultinom.

- JAGS: dmulti

Multinomial distribution

\(X = (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_k)\) a multivariate random variable recording the number of events in each category

If \((n_1, n_2, \ldots, n_k)\) is the observed number of events in each category, then:

\(P((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_k) = (n_1, n_2, \ldots, n_k)) = \frac{n!}{n_1!n_2! \cdots n_k!}p_1^{n_1}p_2^{n_2}\cdots p_k^{n_k}\)

Poisson Distribution: \(N_t \sim Poisson(\lambda)\)

Let \(N_t\) = number of events occurring in a time interval of length \(t\). What is the probability of observing \(k\) events in this interval?

\[P(N_t = k) = \frac{\exp(-\lambda t)(\lambda t)^k}{k!}\]

Events in 2-D space, if events occur at a constant rate, the probability of observing \(k\) events in an area of size \(A\):

\[P(N_A = k) = \frac{\exp(-\lambda A)(\lambda A)^k}{k!}\]

If \(A\) or \(t\) is constant:

\[P(N = k) = \frac{\exp(-\lambda )(\lambda)^k}{k!}\]

Poisson distribution

- Single parameter, \(\lambda\) =

lambda. - \(E[X] = Var(X) = \lambda\)

- R: dpois, ppois, qpois, and rpois.

- JAGS: dpois

Examples:

- Spatial statistics (null model of “complete spatial randomness”“)

- Can be motivated by random event processes with constant rates of occurrence in space or time

Poisson distribution

Suppose a certain region of California experiences about 5 earthquakes a year. Assume occurrences follow a Poisson distribution. What is the probability of 3 earthquakes in a given year?

Geometric Distribution

Number of failures until you get your first success.

\[f(x) = P(X = x) = (1-p)^xp\]

- Parameter = \(p\) (probability of success)

- Range: {0, 1, 2, …}

- \(E[X] = \frac{1}{p} -1\)

- \(Var[X] = \frac{(1-p)}{p^2}\)

- *geom

Negative Binomial: Classic Parameterization

\(X_r\) = Number of failures, \(x\), before you get \(r\) successes; \(X_r \sim\) NegBinom(\(p\))

- Total of \(n = x+r\) trials

- Last trial is a success (\(p\))

- The preceding \(x+r-1\) trials had \(x\) failures (equiv. to a binomial experiment)

\(P(X = x) = {x+r-1 \choose x}p^{r-1}(1-p)^xp\)

or

\(P(X = x) = {x+r-1 \choose x}p^{r}(1-p)^x\)

- \(E[X] = \frac{r(1-p)}{p}\)

- \(Var[X] = \frac{r(1-p)}{p^2}\)

Ecological Parameterization

Express \(p\) in terms of mean, \(\mu\) and \(r\):

\[\mu = \frac{r(1-p)}{p} \Rightarrow p = \frac{r}{\mu+r} \text{ and }\]

\[1-p = \frac{\mu}{\mu+r}\]

Plugging these values in to \(f(x)\) and changing \(r\) to \(\theta\), we get:

\(P(X = x) = {x+\theta-1 \choose x}\left(\frac{\theta}{\mu+\theta}\right)^{\theta}\left(\frac{\mu}{\mu+\theta}\right)^x\)

Then, let \(\theta\) = dispersion parameter take on any positive number (not just integers as in the original parameterization)

Negative Binomial: \(X \sim\) NegBin(\(\mu, \theta\))

\(P(X = x) = {x+\theta-1 \choose x}\left(\frac{\theta}{\mu+\theta}\right)^{\theta}\left(\frac{\mu}{\mu+\theta}\right)^x = \frac{(x+\theta-1)!}{x!(\theta-1)!}\left(\frac{\theta}{\mu+\theta}\right)^{\theta}\left(\frac{\mu}{\mu+\theta}\right)^x\)

- \(E[X] = \mu\)

- \(Var(X) = \mu + \frac{\mu^2}{\theta}\)

- In r: *nbinom, with parameters (

prob= p,size= \(n\)) or (mu= \(\mu\),size= \(\theta\)) - JAGS: dnegbin with parameters (\(p\), \(\theta\))

Overdispersed relative to Poisson (Var(x)/E[x] = 1 + \(\frac{\mu}{\theta}\)) versus 1 for Poisson

Poisson is a limiting case (when \(\theta \rightarrow \infty\))

Negative Binomial

Its appeal for use as a probability generating mechanism in ecology includes the following.

- Allows for non-constant variance typical of count data.

- It often fits zero-inflated data well (and much better than a Poisson distribution).

- It respects the discreteness of the data (no need to transform).

- It can be motivated biologically - e.g.:

If: \(X_i \sim\) Poisson(\(\lambda_i\)), with \(\lambda_i \sim\) Gamma(\(\alpha,\beta\)), then \(X_i\) has a negative binomial distribution.

Continuous Uniform

If observations are equally likely within an interval (A,B):

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{b-a}\]

- Two parameters (a, b)

- Model of ignorance for prior distributions

- \(E[X] = (a+b)/2\)

- \(Var(X) = \sqrt{(b-a)^2/12}\)

- *unif

- JAGS: dunif(lower, upper)

Gamma Distribution: \(X \sim\) Gamma(\(\alpha, \beta\))

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(\alpha)}x^{\alpha-1}\beta^\alpha\exp(-\beta x)\]

- Range 0 to \(\infty\)

- \(\Gamma(\alpha)\) is a generalization of the factorial function (!) that we’ve seen earlier

- \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are parameters \(>\) 0.

- \(E[X] = \frac{\alpha}{\beta}\)

- \(Var[X] =\frac{\alpha}{\beta^2}\)

- R: *gamma

Beta Distribution: \(X \sim\) Beta(\(\alpha, \beta\))

\[f(x) = \frac{\Gamma(\alpha+\beta)}{\Gamma(\alpha)\Gamma(\beta)}x^{\alpha-1}(1-x)^{\beta-1}\]

- ranges from 0 to 1.

- \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are parameters \(>\) 0.

- \(E[X] = \frac{\alpha}{\alpha+\beta}\)

- \(Var[X] =\frac{\alpha}{(\alpha+\beta)^2(\alpha+\beta+1)}\)

- R: *beta

Exponential: \(X \sim\) Exp(\(\lambda\))

\[f(x) = \lambda \exp(-\lambda x)\]

- Range 0 to \(\infty\)

- \(\lambda > 0\)

- \(E[X] = \frac{1}{\lambda}\)

- \(Var[X] =\frac{1}{\lambda^2}\)

- R: *exp

Distributions

How do we choose an appropriate distribution for our data?

- Presence-absence (0,1) at M sites \(\rightarrow\) Bernoullli/Binomial distribution

- Counts, fixed number of sites/trials/etc \(\rightarrow\) Binomial distribution

- Counts, in a fixed unit of time, area

- Normal distribution if the counts are large

- Poisson distribution: if \(E[Y |X] \approx Var(Y|X)\)

- If \(Var(Y|X) > E(Y|X)\): Negative Binomial, Quasipoisson, Poisson-normal model

- Continuous response variable: normal distribution (usual default)

- gamma (if \(Y\) must be \(> 0\))

- lognormal (if skewed data)

- Time to event: exponential, Weibull

- Cicular data (\(-\pi, \pi\)): von Mises

Other useful information

For a diagram showing links between distributions, see:

Diagram of distribution relationships

Want to visualize different statistical distributions, check out this link.

Note that some can be written in multiple ways:

For example, gamma:

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(\alpha)}x^{\alpha-1}\beta^\alpha \exp(-\beta x)\]

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(\alpha)\beta^\alpha}x^{\alpha-1}\exp(-x/\beta)\]